Think Slow, Act Fast: The Paradox of Project Planning

How Big Things Get Done (ch1)

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 6 min read

In the book How Big Things Get Done, Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner presented an analysis of why large projects fail to meet their objectives. As someone who has witnessed the ups and downs of loads of projects, I’m very curious to learn what we can do better.

One of the overarching themes of the first chapter is their thesis of “think slow, act fast.”

The Iron Law of Megaprojects

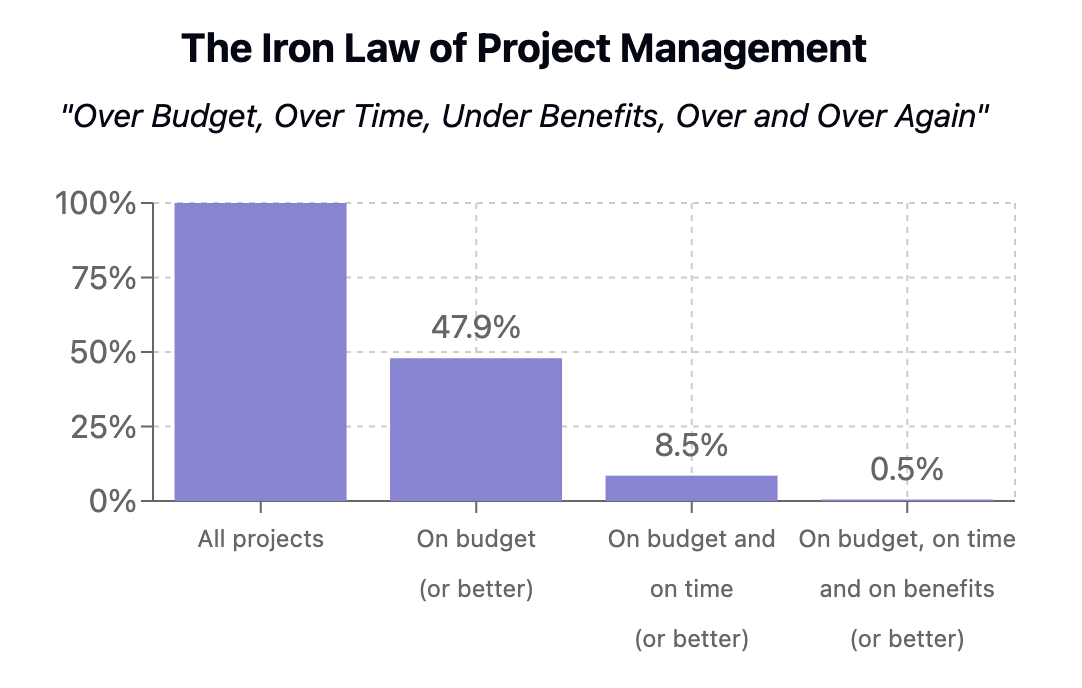

Flyvbjerg and Gardner share what they term the “iron law of megaprojects,” highlighting an uncomfortable reality: projects are consistently over budget, over time, and under deliver on benefits. It’s backed by an extensive database of over 16,000 projects across 136 countries and 20 different fields. The statistics are quite convincing:

- Only 47.9% of projects remain on budget.

- A mere 8.5% achieve both budget and time targets.

- Just 0.5% deliver on budget, on time, and with promised benefits.

These figures are a wake-up call for anyone involved in project management, especially those of us who pitch for funding. While all projects start with plans and expectations, the reality is that we are kind of fooling ourselves. These statistics show that project planning is actually pretty rough in the real world.

The Fat Tail Problem

What makes these statistics particularly concerning is the distribution of project outcomes. Project overruns don’t follow a normal distribution; they exhibit what the authors call “fat tails.” In IT projects, for instance, 18% experience cost overruns above 50%, with these projects averaging a 447% overrun. This pattern is not unique to IT; it extends to pretty much every sector. In their words:

Information technology is truly fat tailed. So are nuclear storage projects and the Olympic games and nuclear power plants and big hydroelectric dams as our airports, defence projects, big buildings, aerospace projects, tunnels, mining projects, high speed rail, urban rail, conventional rail, bridges, oil projects, gas projects and water projects.

Examples of Fat Tail Overruns:

- Boston’s Big Dig: Tripled its planned cost.

- James Webb Space Telescope: Reached 450% of the original budget.

- Scottish Parliament: Overran by 978% and was three years late.

- HS2 (High Speed 2): The UK’s high-speed rail project has seen its budget triple and completion dates pushed back by several years.

These extreme outcomes are far more common than traditional risk management approaches account for. Adding percentage-based contingencies to budgets, such as a 62% buffer for major building projects, fundamentally misunderstands the nature of project risk. The fat-tailed distribution means that extreme overruns are not outliers but rather expected occurrences.

As somebody who has to pitch for funding on occasion, my instinct would be to definitely not tell my funders that my project is likely to fail, and it’s likely to fail significantly over budget, over time, and under benefits. So this paradox, I think, has to be resolved.

If we believe in reality, and we don’t believe ourselves to be superhuman, then should we not accept that and present that risk as real? And yet anybody who’s ever had to ask for funding has to know that if they were to say that, you’d never get funded.

The Window of Doom

The authors introduce a metaphor: project duration is like an open window through which problems can enter. The longer the window stays open, the more opportunities there are for disruptions, including unpredictable “black swan” events that can derail the entire project.

Their proposed solution centres on what they call “Pixar planning approach”: extensive planning followed by rapid execution. They argue against both inadequate planning and the tendency to rush into execution. For example, the California High-Speed Rail project is criticised for producing numerous documents and figures that created the illusion of planning without providing a “carefully detailed, deeply researched, and thoroughly tested programme.” Similarly, HS2 has faced criticism for its extensive planning phases that have not translated into timely and budget-conscious execution.

I know Agile gets a bad rep these days because people have seen that it isn’t a magic bullet and it’s easy to mess up. My experience is that sometimes Agile projects are, if anything, too rigid to a methodology like Scrum and not aligned really with the thesis of Agile, which is to respond to things and not over-commit to, assuming you get everything right up front. But at least Agile (with the capital A) acknowledges the reality of there being surprises and it attempts to put into place a process to deal with those surprises. So I have to say I’m very curious to see the authors’ thesis of how to emphasise significant planning prior to execution without pretending that we’re not going to hit these surprises in the real world.

The Planning Paradox

This prescription—planning extensively before acting—seems to me to echo the “big plan upfront” approaches that fell out of favour with the rise of agile methodologies. Big Plan Upfront / Waterfall approaches fall out of favour for a good reason. I doubt the authors are naive to the problems with that approach, so I’m very curious to see what they actually think we should do.

The break-fix cycle they describe—where inadequate planning leads to continuous problem-solving during execution—is a familiar pattern to many project managers. They use the metaphor of a woolly mammoth stuck in a tar pit to illustrate how any project that enters this loop is stuck.

thingsithinkithink

-

Seeing just how bad things are when it comes to projects is a bit of a surprise to me. I know there’s something of a reputation around IT projects in particular being harder than they look. But I don’t think I’d realised just how pervasive the problem was and across different sectors.

-

The metaphor around the fat tail is very apt and gives me a way to understand why we aren’t able to use average overruns as a way to appropriately budget. Of course, it doesn’t resolve the question of how much we should budget for overruns.

-

If we take the actual overrun value for IT projects, and if we were to put that into our project pitches, we would never get funded. (gulp)

-

I’m very curious to see how they resolve Big Plan Upfront against the reason we came up with Agile. You discover that you don’t know what you don’t know and you cannot plan everything upfront. So I can’t wait to see how they resolve that paradox.

-

This first chapter reminds me of Mark Cerny’s Method, which is widely used in (or at least was widely used when I was in the scene) for game development, particularly at Sony. I know that Richard LeMarchand from Naughty Dog, who is now at USC, advocates that approach under the term pre-production, where planning takes the form of lots of little prototypes and experiments that prove certain things. At a workshop I attended once, he said that really, once you hit real production, pretty much nothing should change. The pre-production method emphasises solving all of the challenges before you scale up, so that you can hit the ground running in execution, which I think is something of a compromise between the waterfall big plan upfront versus Agile worlds. I’m curious to see if this book proposes something similar.