Why we need Experiment-based Roadmaps in the AI Product Era

Why evaluation-driven experimentation creates better roadmaps in AI products.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 6 min read

I recently watched a good talk by Bryan Bischoff, Head of AI at Theory Ventures, on why traditional product roadmaps fail for AI development and how teams should approach building AI capabilities differently. The presentation provided a good mental model for shifting from rigid planning to experimental discovery.

The Problem with Traditional Roadmaps in AI

Traditional software roadmapping focuses on time estimates for when specific features will be ready for users. Product managers meticulously plan sprints, assign engineers to swim lanes, and establish checkpoints to track progress. When teams fall behind, they reassess, potentially cutting scope or adjusting timelines.

This approach works well for conventional software development where the paths are well-trodden. But as Bischoff argues, it falls apart in the context of AI:

Your goal is to discover new territory. Why do you think your routes will get you there?

The fundamental issue is that you cannot roadmap what hasn’t been discovered. When building AI features that venture into uncharted territory, the rigid structure of traditional roadmaps becomes an impediment rather than an aid.

Roadmaps have traditionally functioned as ledgers that stakeholders “transact against” – tracking days spent against projected completion dates. But AI development doesn’t work this way. Items on roadmaps aren’t fungible; some carry substantially more value or risk than others, and their development paths aren’t predictable.

Starting with Questions, Not Features

Instead of planning features, Bischoff proposes starting with questions through an experiment-driven approach. Great experiments begin with hypotheses, which are fundamentally questions.

Consider these contrasting approaches to the same development task:

Feature: “Build keyword index of row values”

Experiment: “Can we find relevant tables for NL2SQL by the row values inside them?”

The first approach prescribes a solution without validating the problem. The second acknowledges uncertainty and creates a framework for learning.

Other examples include:

- “Does data extraction work better before OCR transcription or after?” versus “New transcription node in extraction pipeline”

- “Does an ‘importance judge’ work better on summaries?” versus “Epic: Summarize conversations”

- “Should we rerank or interleave our RAG results?” versus “Seven meetings with vendors about why their reranker is SOTA”

This shift requires genuine curiosity. You can’t just obsess over “making AI done”; you must care about discovering what works and why.

Moving Beyond Questions to Metrics

Questions alone aren’t enough. The next step is identifying how you’ll measure success. For each hypothesis, define metrics that quantify progress:

- “What is our table recall?” (The percentage of queries where relevant results appear in retrieval)

- “How do accuracies change for each extracted attribute?”

- “Is the binary accuracy on this classification task higher?”

- “Does the rank of the necessary resource significantly affect generation?”

More importantly, teams need to estimate the expected effect size for these metrics. This is challenging and I think our instinct is to resist it - but it’s valuable work:

- “We correctly retrieve the right table 73% of the time on queries; this approach can have a single-digit percent improvement”

- “We currently extract 40% of attributes correctly; this could add 10% accuracy across our dataset”

- “Where RAG succeeded, generations fail 15% higher when the relevant doc is central in retrieval; reranking could put them first 60% of the time”

These estimates transform vague hypotheses into actionable experiments with quantifiable ROI. They allow teams to plot initiatives on an effort-versus-impact matrix, enabling rational prioritisation.

Evaluation-Driven Development

To operationalise this experimental approach, Bischoff advocates for evaluation-driven development. Great evaluations don’t simply answer whether an AI capability works; they reveal which assumptions are false.

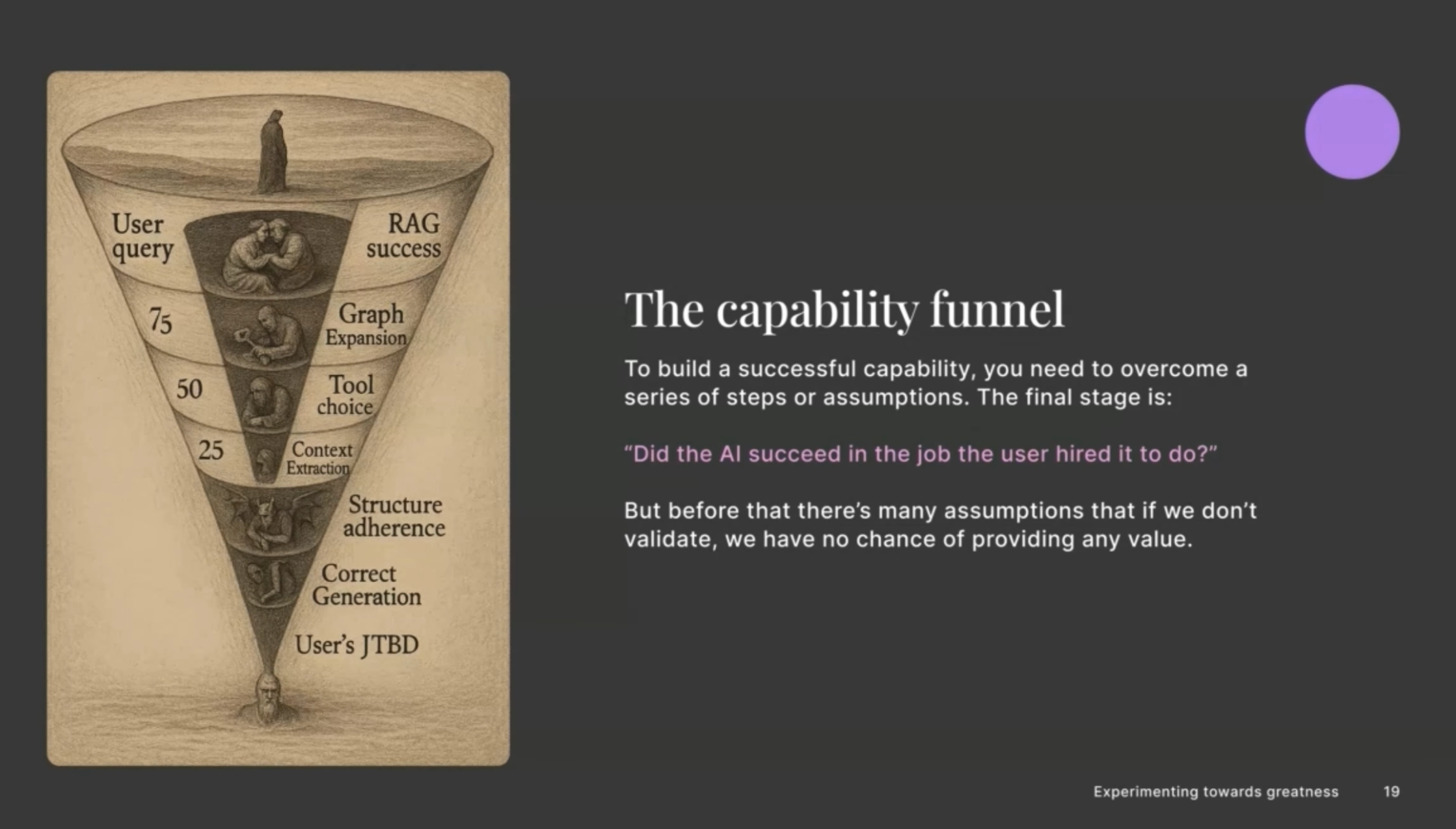

The “capability funnel” illustrates this concept. To build a successful AI capability, you must overcome a series of steps or assumptions. The final stage – “Did the AI succeed in the job the user hired it to do?” – is just the culmination of many preceding assumptions that must hold true.

Take a natural language to SQL feature. Before asking if it successfully answers user queries, you must validate several assumptions:

- Can it generate syntactically valid queries?

- Can it generate queries that execute without errors?

- Do the queries return relevant results?

- Do the queries match the user’s intent?

- Do the queries solve the user’s actual problem?

Users often fail to precisely articulate their problems. When someone asks, “What is our ARR?” they likely need more than a single number – they might need the figure broken down by segment or tracked over time. Great AI systems recognise these implicit needs.

The Failure Funnel as a Guide

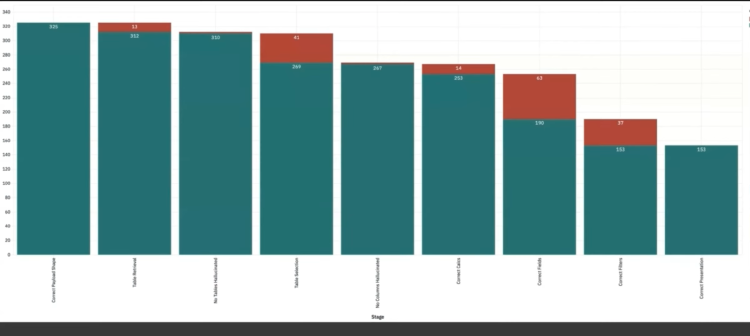

The most valuable insight from evaluations comes from what Bischoff calls the “failure funnel” – a systematic analysis of where and why your AI pipeline breaks down. This reveals which components most urgently need improvement.

(see the image at the top of the post…)

Importantly, failures at the beginning of the pipeline have outsized impacts. If the system fails to retrieve the right document at step one, it has no chance of succeeding in subsequent steps. Fixing upstream failures often uncovers new ones downstream.

The failure funnel doesn’t just identify problems; it serves as the breeding ground for your next experiments:

Your evals, and especially the funnel of failures, point to questions; those questions suggest the hypotheses; and the hypotheses beget the experiments.

This creates a virtuous cycle: evaluations generate questions, which lead to hypotheses, which drive experiments, which improve your capability funnel.

Implementing This Approach in Practice

Adopting this experimental mindset involves a significant shift for many organisations. When asked how to get stakeholders on board, Bischoff offers a pragmatic reframing:

Instead of promising that a product will work (a risky proposition for novel AI), promise to make progress on the most impactful parts of the problem. This significantly de-risks the engagement while providing a clear framework for demonstrating progress.

One approach is to start with your most important capability that has existing evaluations. Build the failure funnel for it, then present the results to leadership. Showing precisely where and why systems fail creates a more productive conversation about prioritisation than abstract feature discussions.

People want roadmaps to be dates that prescribe how engineers spend their time. This is failures that prescribe how engineers should spend their time.

thingsithinkithink

-

This approach resonates strongly with my experience building AI products. Feature-driven is risky when you’re pushing boundaries. I have worked on projects where the team wasted a lot of time pushing for features that weren’t the best use of time.

-

I’ve seen many projects fail because they jumped straight to implementing solutions without validating underlying assumptions. The capability funnel + failure funnel gives us a structured way to identify these assumptions and test them methodically.

-

There’s tension between this experimental approach and the commercial realities of consulting or product development. Clients and stakeholders want certainty, but promising certainty with novel AI is disingenuous. We need better frameworks for communicating this reality without scaring people off. (see Strategic Misrepresentation)

-

What’s powerful about Bischoff’s Failure Funnel is that it doesn’t just acknowledge uncertainty – it embraces it as the source of pathfinding. The best teams aren’t those that pretend to know everything at the outset; they’re the ones with the most effective learning mechanisms and willingness to adapt.