Three Things I Learned About Voice Agents from Kwindla Kramer

Three thigns I learned about voice agent architecture, context limitations, and latency trade-offs.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 3 min read

I learned three things from this interview with Hamel Husain and Kwindla Kramer, founder of PipeCat, an open-source framework for voice and multimodal conversation. As someone who hasn’t worked much with voice agents, I found three things particularly interesting.

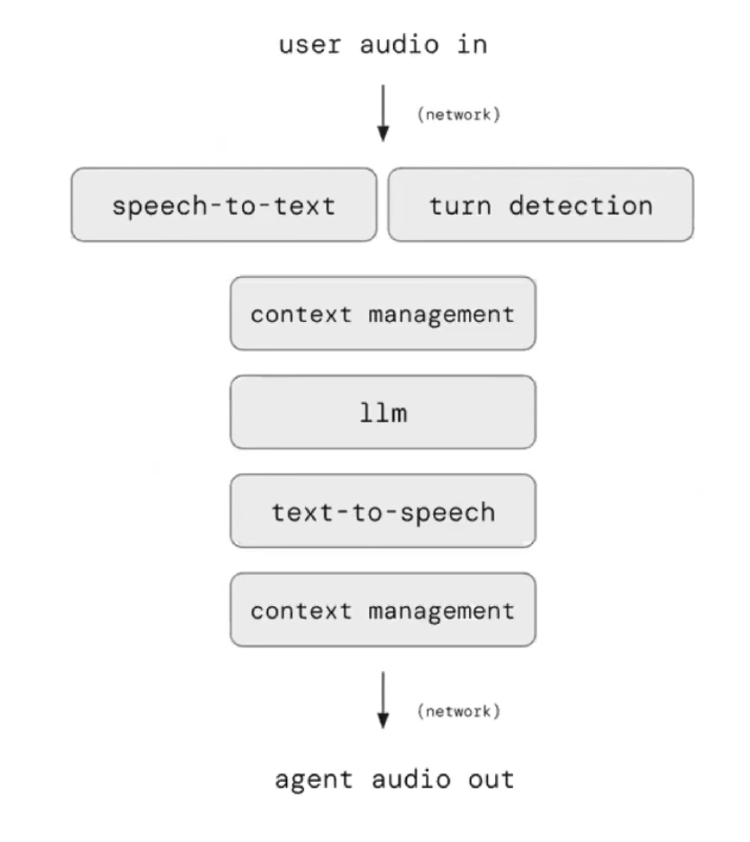

Voice Agents Use Traditional Pipelines, Not Fancy Models

The first thing was learning that most production voice agents don’t use the latest speech-to-speech models from OpenAI or Google (etc). Instead, they rely on a modular pipeline approach that breaks the process into discrete steps.

The standard architecture works like this: audio comes in and gets processed through speech-to-text conversion whilst simultaneously running turn detection. Turn detection is what bridges the gap between a rubbish agent and something that feels modern - it determines when the agent should speak. The text goes through context management into an LLM, which generates a response. That response gets converted back to speech via text-to-speech and sent to the user, with the context updated for the next turn.

As somebody who hasn’t worked with voice agents myself, but pays close attention to model improvements, I would have expected that the proper speech-to-speech models would be starting to become the dominant technology. It’s interesting to see that whilst those speech-to-speech models grab the attention and get headline coverage, the vast majority of voice agents are powered by what you’d build yourself: speech-to-text, LLM processing, then text-to-speech.

Models Degrade Faster Than Expected in Multi-Turn Voice

Kwindla highlighted how quickly voice agents go out of distribution, despite operating within theoretical context window limits. The issue isn’t context length but the nature of the training data:

“Long multi-turn, long contexts in general, and audio all tend to take you out of distribution for how the big models are trained today. Practically speaking, what that means is that instruction following and function calling are worse for voice AI use cases than they are on any of the published benchmarks you will see for any models.”

Tool calling degrades significantly as conversations progress. Models might handle function calls perfectly for the first few turns, then performance falls off a cliff. This happens because training data contains little that resembles long back-and-forth conversations with extensive tool usage.

This reinforces how each use case requires deep understanding of what’s at stake. You can’t simply integrate an LLM and expect consistent performance across different interaction patterns.

Latency Forces Infrastructure Trade-offs

The third thing I noticed concerned the geographical challenges of voice agent deployment. Latency matters enormously - Kwindla recommends targeting 800 milliseconds voice-to-voice response time.

This creates a dilemma: you want to be close to customers to minimise network latency, but you also need proximity to the AI providers you’re calling repeatedly. Since major LLM providers don’t have nodes everywhere, you must choose between customer proximity and provider proximity.

Because voice agents make multiple inference calls per interaction, teams typically choose to locate near LLM provider endpoints rather than customers. The computational latency outweighs the network latency to users.

- Tags:

- Voice-Agents

- AI

- Infrastructure