Three Ways I Think Frameworks are Good (actually)

Are frameworks actually useful? Exploring how they enable communication, engagement, and focused thinking

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 5 min read

A recent conversation with my friend Dr Jon Sykes sparked some thoughts about where frameworks derive their value. The conversation started with a question: is the benefit of frameworks really just that they create a shared language? We were discussing my review of Chapter 2 of “How Big Things Get Done” and examining the framework that is emerging from my reading so far. This led us to identify three distinct sources of value in frameworks.

Creating a Shared Language

The first value of frameworks lies in providing terminology to discuss concepts. Reading Chapter 2 of “How Big Things Get Done” gave me the term “strategic misrepresentation.” While I recognised the concept from my own experience, I lacked precise language to discuss it. Even a basic framework with definitions and criteria enables meaningful communication by establishing boundaries around the topics we discuss.

Without the language offered by a framework, we have to spend so much time trying to create boundaries around what we’re actually trying to talk about that it forces us to lack precision. We waste time just trying to get on the same page when we could be getting to the actual meat of the matter.

The ‘Magic Circle’ of Engagement

The second source of value parallels a concept from game design. Johan Huizinga’s “magic circle”, later popularised by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman in “Rules of Play”, describes how meaningful play emerges from the intersection of three elements. A football pitch illustrates these perfectly:

- Physical Space: You can’t play football without a pitch - the physical boundaries define where the game can take place

- Temporal Moment: The pitch isn’t always a football pitch - it’s just grass until the game begins

- Mental State: When a ball crosses the goal line during play, it constitutes a point - but this meaning only exists because players have agreed to the rules and significance of the game

This same principle applies to frameworks. Merely ticking boxes or following procedures without mental engagement yields little value. You must build a mental model of the framework’s purpose and commit to it wholeheartedly.

A personal experience illustrates this point rather well. In the first year of my PhD, I was given full responsibility for a module - quite unusual for someone at my level. I wrote and delivered all the lectures, tutorials, seminars, and practicals, marked the exams and coursework - the whole lot. When my first sitting results came in at 82% pass rate, it fell below the university’s target threshold, and I was asked to create an action plan detailing improvements.

Teaching my first full module, you can imagine I was quite intimidated and concerned. I spent two weeks genuinely reflecting on my module, poring over student comments, researching pedagogical approaches and techniques. I returned with a rigorous, multi-page plan detailing changes to materials, teaching methods, and assessment strategies.

A few days later, when I presented this comprehensive plan to a senior member of staff, I asked about next steps - would I receive feedback? Face a review panel? His response was memorable:

David, it’s your job to write it, and it’s my job to collect it. It’s nobody’s job to read it.

Some colleagues, knowing this reality, put minimal effort into such exercises. But my genuine engagement with the framework, despite its performative nature, led to valuable insights and improvements.

Like the magic circle in games, frameworks only work when we truly commit to them.

Permission to Focus

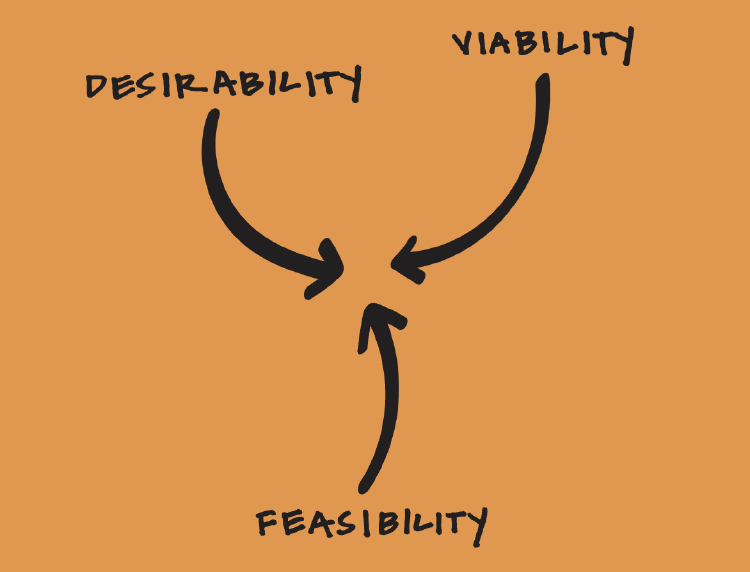

The third value of frameworks comes from their ability to grant permission to ignore certain aspects of a problem. This mirrors Jesse Schell’s approach in “The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses,” where designers examine their work through specific perspectives, like narrative or mechanics.

The value isn’t just in what these lenses highlight - it’s in what they allow us to temporarily ignore.

Given our limited cognitive capacity, the ability to focus deeply on one aspect while setting aside others proves invaluable. A framework doesn’t need to be comprehensive to serve this purpose; sometimes its greatest value lies in helping us narrow our focus.

This approach continues to show merit. Design firm IDEO pioneered the use of different lenses in their design thinking methodology, helping teams look at problems from distinct perspectives. Jesse Schell later brought this approach to game design, formalising it into his collection of lenses.

My PhD student, Karen Shanks, is developing specialised lenses for health behaviour change game designers that focus on motivation frameworks. Her work bridges psychological principles with practical game design, creating tools that help designers embed core psychological concepts into their mechanics. Rather than trying to tackle every aspect of behaviour change game design simultaneously, these lenses allow designers to focus specifically on how their design choices influence player motivation and health outcomes.

Karen’s research demonstrates how frameworks can evolve beyond theoretical constructs into practical tools. By developing specific lenses for motivation in behaviour change games, she’s showing how focused frameworks can help designers create more impactful interventions. Her work represents a practical application of the principle that sometimes the most valuable aspect of a framework is what it allows us to temporarily set aside.

thingsithinkithink

- that story I shared about my first year teaching a module sticks with me because it showed me for the first time how many of our best ideas are undone by cynicism.

- I think about it a lot

- I love me a good framework. It doesn’t have to be perfect or complete to be very useful.

- Tags:

- Frameworks

- Blog

- Feature