Synthesising a new framework for AI Transformation

I like bits of Brunig's and Mollick's AI frameworks, but neither quite works for me.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 10 min read

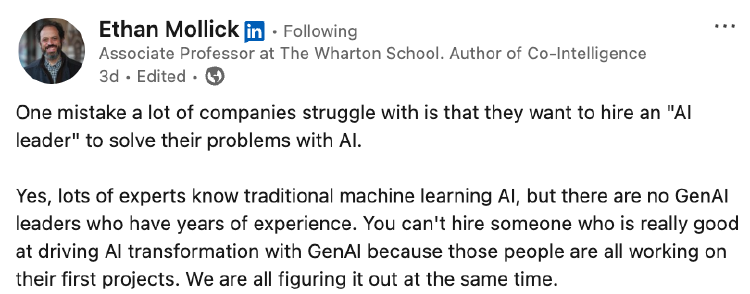

Sparked by Ethan Mollick’s post about AI transformation, I’ve been thinking about how we frame AI’s role in workplace transformation. My current role involves doing this kind of work, and Ethan is correct to say we’re all figuring it out at the same time. Therefore, in that light, here are some things I’ve been thinking about lately.

I’ve been considering two frameworks: Drew Brunig’s categorisation of AI use cases as Cogs, Interns, and Gods, and Ethan Mollick’s organisation of tasks into Automated, Delegated, and Just-Me categories.

Both frameworks can be useful shorthands, but I find the “Gods” label unnecessarily sensational. In practice, we’re dealing with tools, not deities. I prefer the metaphor/classification Colleagues for AI systems we trust to work independently, keeping our focus on the practical rather than the apocalyptic.

Likewise, in Ethan’s framework, I feel “Delegated” doesn’t evoke the human/AI dynamic that “Intern” does. So I’ve been trying to find a way to bridge both frameworks to help us do this kind of work.

The Core Mapping

| Brunig (my edit) | Mollick | Key characteristic | Human involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cogs | Automated tasks | Focused single function | Set it and forget it |

| Interns | Delegated tasks | Grunt work supervised by responsible humans | Review, corrections, key decision making |

| Colleagues | Just-Me tasks | Complex judgement or human domains | Full ownership (for now) |

I’m going to work through this and try to show where I think we land when bringing these ideas together.

Cogs: The Automated Components

In Brunig’s framing, Cogs are “designed to do one task, unsupervised, very well.” They’re comparable to functions that fit within larger systems, with each cog designed for “one task and a low tolerance for errors.”

These map cleanly to Mollick’s Automated Tasks – “ones you leave completely to the AI and don’t even check on.” Both describe focused, reliable components that perform specific functions without human intervention:

- Extracting postcodes from forms

- Converting speech to text in meeting recordings

- Classifying customer emails by urgency

What makes these “cog-like” and automatable is their narrow focus and integration into larger processes. They run reliably enough that we don’t need to watch them constantly, freeing up human attention for more complex work.

As Brunig notes, cogs are usually built with “fine-tuned or heavily prompted small, open models.” They’re economical and purpose-built for reliability rather than versatility. However, the flexibility of large language models is leading to a “big hammer, everything looks like a nail” pattern. I’ve already seen this happening in organisations that weren’t previously AI-oriented - tasks like sentiment analysis or entity extraction that traditionally required specialized models are now being handled by general-purpose LLMs (albeit smaller ones) instead of custom-trained models. This doesn’t refute Brunig’s point, but suggests the tools used for cog-like tasks are evolving.

Interns: The Supervised Assistants

The way I think about this intern level is that there’s a relationship between a supervising human and an AI doing bits of work for them. When Ethan talks about jobs being comprised of bundles of tasks, it’s these bundles that we delegate to the AI and then review. These bundles can include simple cogs but also more advanced tasks that are less reliable.

This is where I see today’s “agents” fitting in. An agent isn’t just a single cog - it’s a collection of capabilities bundled together to accomplish broader goals. For example, a research agent might:

- Search and retrieve relevant documents

- Extract key information from PDFs

- Summarise findings in a consistent format

- Draft responses based on the research

Each component could theoretically be a separate cog, but wrapped together they form what we delegate as a bundle. The human remains responsible for reviewing the output and making key decisions, particularly when the agent encounters edge cases or ambiguity.

What’s particularly valuable in thinking about bundles is that it helps us see the layers of AI workplace integration. Individual cogs can disappear into pipelines, while collections of cogs plus more advanced capabilities can be packaged as agents or delegated task systems. The human role shifts from performing each task to orchestrating and supervising these bundles.

As Mollick notes in his work, this seems to be where most productive human-AI collaboration currently happens - not with fully autonomous systems, but with responsible humans delegating grunt work while maintaining oversight and decision authority.

From Gods to Colleagues: A Reframing

As mentioned, I don’t like the framing of highly competent AI as “Gods” - “super-intelligent artificial entities that do things autonomously.” I think Colleagues better captures what we’re aiming for: systems that can work alongside us with minimal supervision while still operating within human systems and towards human-defined goals.

That said, an important reality check: despite all the lab announcements and AGI predictions, we’re simply not there (yet). Those of us building systems on top of these AI models aren’t likely to be interacting with truly autonomous human-level systems in the immediate future. The practical applications of AI in workplaces today don’t include handing over full human-level jobs to AI systems.

Therefore, when using Brunig’s framework of cogs, interns, and colleagues, my opinionated stance is that we can mostly ignore (for now) the idea of just handing over complete jobs to AIs. Instead, I find it more useful to focus on which parts of our work can be reconstituted as cogs or as interns (bundles of delegated tasks with human supervision).

The Just-Me Tasks versus Colleagues (Gods)…

This is where Mollick’s framework is particularly valuable. He addresses the most advanced layer differently by pointing out that there are tasks we just wouldn’t ask an AI to do - he calls them “Just-Me Tasks.”

While Brunig’s “Gods” category focuses on hypothetical future AI with fully autonomous capabilities, I find Mollick’s approach more immediately practical and fundamentally more useful.

Since I believe the intern level (delegated tasks) is where most near-term value will come from, I think it’s more useful to characterise the third layer in terms of what stays human rather than what becomes fully automated.

1. Beyond the Jagged Frontier (Temporary Just-Me)

These are tasks that remain human-only because current AI isn’t good enough yet. They sit outside what Mollick calls the “Jagged Frontier” of AI capabilities.

- Complex strategic decision-making requiring deep contextual understanding

- Novel research design drawing on multiple disciplines or lived experience

- Nuanced client relationship management in highly variable situations

The key point here is that some tasks are temporarily in the colleague/just-me layer because of capability reasons.

As AI improves, they won’t suddenly become colleague-level tasks where AI works autonomously. Instead, they’ll move into the intern category first - becoming part of bundles that require human supervision.

2. Principled Human-Essential Tasks

The second category involves tasks we keep human for ethical or fundamentally human reasons – even if AI could perform them competently:

- Deciding on social support eligibility

- Creating art for personal expression

- Making final hiring decisions

These tasks involve values, emotional connection, or ethical accountability that we believe require human ownership. Even if an AI could technically perform them, we choose to maintain human involvement as a matter of principle.

This distinction helps us think about which tasks will forever stay beyond the ownership of AI versus those which are currently beyond the capability of AI but will be brought in over time as models improve.

What Work Looks Like Following AI Automation

Mollick makes an observation that helps tie these frameworks together: “Jobs are composed of bundles of tasks. Jobs fit into larger systems.”

A job title like “analyst” or “designer” is really a shorthand for a collection of responsibilities that exist within organisational contexts. The system aspects are crucial – a task doesn’t exist in isolation but connects to processes, expectations, and relationships.

This systems perspective explains why technological change rarely eliminates entire professions outright. When spreadsheets automated calculations, they didn’t eliminate accountants – they changed the bundle of tasks accountants perform, shifting focus from computation to analysis and strategy.

As AI takes over more tasks, our job descriptions shift from doing each task to ensuring the right outcome:

I’m no longer paid to write perfect documentation; I’m paid to ensure users can successfully achieve their goals.

This reframes seniority and expertise. Junior roles may still focus on reviewing AI outputs, while senior roles become what Mollick describes as “orchestrators of pipelines,” focusing on:

- Which task bundles can be safely automated

- How to measure and improve the quality of AI outputs

- When human intervention is necessary

Organisations undergoing AI transformation will need to both redesign business processes into cogs, task bundles, and supervision points. But they will also have to undergo organisational redesign and job role redesign to remove bottlenecks and ensure smooth transformation.

How to Use AI in Transforming Work

Trying to weave together these various threads into something coherent, here’s where I’m currently landing in terms of how to use AI in transforming work:

| Cogs | AI Interns | Human-Only |

|---|---|---|

| Well-defined tasks that AI performs exceptionally well and can be trusted to do without supervision. These are single-purpose functions with low error rates that can be integrated directly into workflows. Might be agents or LLMs. Might be Machine Learning | Bundles of cogs and other tasks that AI Agents can significantly help with, but which require oversight from a responsible human. These represent collections of related activities where AI does the grunt work but humans make key decisions. Some will be Centaur-like tasks (with clear boundaries between the AI bit and the Human bit). Some will be cyborg taks (where a human pilots an AI and they work on a task together) | Tasks unsuitable for AI involvement. There are two types of activities in this grouping: - (1) Tasks which AI is not currently very capable of doing - these will, over time, move into the Task Bundles layer - (2) Tasks that we decide, for ethical or fundamentally human reasons, should not be done by AI. |

Much of my current work involves helping organisations undergo AI transformation. This is how I’m currently thinking through that process - identifying which activities fit into which category, and designing systems that maximize the value of cogs and interns while preserving human judgment where it matters most.

thingsithinkithink

-

The terminology shift from “Gods” to “Colleagues” isn’t just semantic – it’s grounded. We should be designing for partnership, not for magical genie-out-of-a-lamp replacement.

-

The distinction between skill-boundary and principled human-essential tasks clarifies many confused debates about “jobs at risk.” Some tasks are temporarily human; others are permanently so.

-

Jobs as systems of task bundles offers a much more nuanced view than the binary “will AI replace X profession?” headlines. The question isn’t whether a job will vanish, but how its component tasks will shift across the jagged frontier, and what the job looks like following that transition.

- The above point doesn’t ease the pain of those fields where work has been significantly negatively impacted by abundant access to AI. My friends who are visual artists, graphic designers, and writers are certainly feeling that impact.

-

Regarding my dismissal of “Gods” - I’m not saying AGI will never happen. But there’s a diffusion challenge - how long will it take for the first AGI to be rolled out to every business that needs transformation? That’s why I don’t think those of us building practical systems will be building on true AGI over the next five years. There might be instances here and there, but most of us will be building complex, semi-autonomous, intern-level agents supervised by people with broad contextual understanding of their work environment.

- There’s an absolute boatload of context that human beings have that we have no mechanism to transpose into a simple stream of tokens for even the most advanced AI systems. This isn’t a claim about the timeline of AGI - it’s about when us “normies” will actually be using these models in everyday business contexts.

- Tags:

- Ai

- Transformation

- Framework