Building Domain-Specific Annotation Tools with FastHTML: Lessons from Isaac Flath

How Isaac Flath built a medical flashcard annotation tool for AnkiHub using FastHTML, and why custom annotation tools beat generic ones for complex domains.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 7 min read

I’m writing up my notes from Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s excellent AI Evals course. Today we have Isaac Flath’s (cohort 1) session on building custom annotation tools. Isaac showed how he built a real-world medical flashcard annotation system for AnkiHub using FastHTML. I’ve written before about FastHTML (see FastHTML’s Chrome DevTools integration) and this builds on that with a bit of detil on FastLite db support and some htmx stuff.

The AnkiHub Challenge: Inverted Retrieval at Scale

Isaac’s use case centers on AnkiHub, a medical flashcard platform where students search for study materials.

Their specific challenge is around an inversion of typical retrieval patterns:

- Traditional retrieval: Short queries → long documents

- AnkiHub’s: Long queries → short flashcards

Medical students might type two words or upload entire PowerPoint presentations and book chapters. The system then returns hundreds of flashcards - each containing just one or two sentences designed for memorisation.

The domain requirements make this particularly complex:

- Technical precision matters: Similar isn’t good enough. “Purine” and “pyrimidine” are related but distinct concepts that require different sets of flashcards.

- Variable query lengths: From keywords to 50-page documents (i.e “give me flashcards for this talk”)

- High volume evaluation: One query might return 400+ flashcards requiring individual assessment during the eval iteration loop

Domain-Specific Tools

Generic annotation tools provide broad workflows, but they can’t encode the specific business logic that makes evaluation efficient.

It’s always the case that whatever you’re working on you have a bespoke specific business logic - so you’ll always benefit from that bespoke design.

AnkiHub’s custom workflow includes:

- Multi-stage annotation: Two annotators must review each query

- Disagreement resolution: When annotators disagree, they re-evaluate and justify their decisions

- Dual evaluation: They assess both result quality AND query quality (e.g., “heart” is too generic to be useful - how many thousands of flash cards would be returned - zero value there)

- Status tracking: Clear visibility into annotation progress across the team

Generic tools force you into their assumptions about how annotation should work. Custom tools let you encode your domain expertise directly into the interface.

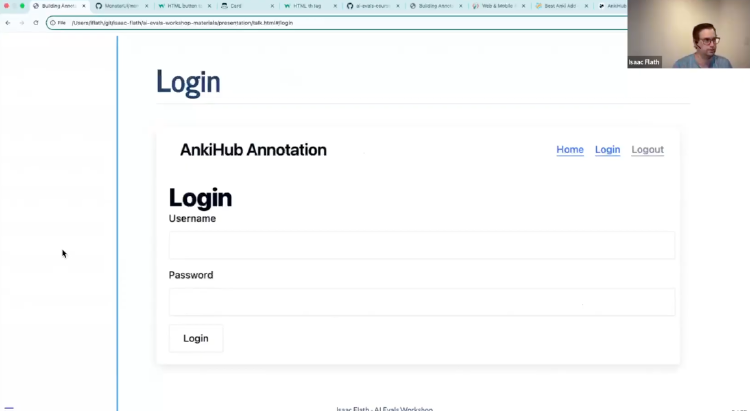

FastHTML: Staying in Python Context

I know that experienced web folks won’t find the idea of a minimalist, python web app builder appealing, but I like how you don’t have to switch langauge / framework context when you use FastHTML.

As Isaac put it: “If you’re living in Python, it helps you stay in that context.” No separate HTML files, CSS files, or wrestling with JavaScript frameworks.

Here’s his minimal example:

from fasthtml.common import *

from monsterui.all import *

app, rt = fast_app(hdrs=Theme.blue.headers())

@rt

def index():

return Container(H1("Hello World"))

serve()

You run python main.py and immediately have a server running at localhost. No build steps, no configuration files.

Database Setup with FastLite

Isaac uses FastLite for database access, which builds on python’s in-build SQLite implementation and follows the same minimal-code philosophy as FastHTML. The annotation table schema is simple:

from fastlite import Database

db = Database('eval.db')

@dataclass

class Annotation:

input_id: str

document_id: int

input: str = None

document: str = None

notes: str = None

eval_type: str = None

That’s it. No ORM complexity, no Docker containers running PostgreSQL. Built-in SQLite handles everything for small annotation tools. As Isaac said: “FastLite does the same thing for databases that FastHTML does for websites - minimum amount of code, maximum amount of productivity.”

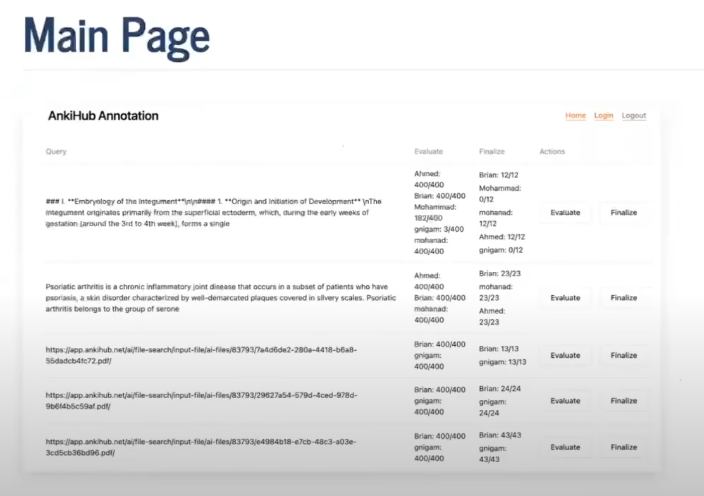

The Main Page: Routes and Tables

FastHTML’s routing works differently from FastAPI. Instead of explicit route strings, it uses function names with a decorator:

@rt

def index(): # Becomes the root route "/"

# Get unique queries from database

unique_inputs = list(db.annotations.rows_where(select='distinct input_id, input'))

body = []

for unique_input in unique_inputs:

body.append({

'Input': f"{unique_input['input'][:125]}...",

'Action': A("Evaluate",

cls=AT.primary,

href=evaluate.to(input_id=unique_input['input_id']))

})

return Container(

H1("Evaluation Index"),

TableFromDicts(['Input', 'Action'], body)

)

Also note the helper function TableFromDicts that generates HTML tables from Python dictionaries.

Also note evaluate.to() which creates links to other Python functions with parameters. This is quite nice - instead of hardcoding URLs or manually building query strings, FastHTML generates the correct URLs based on the function signature. So evaluate.to(input_id="123") becomes /evaluate?input_id=123 automatically, and you get type safety because it knows what parameters the function expects.

These aren’t heavy abstractions - they map directly to HTML elements. A button in FastHTML is an HTML button, just with Python syntax instead of angle brackets.

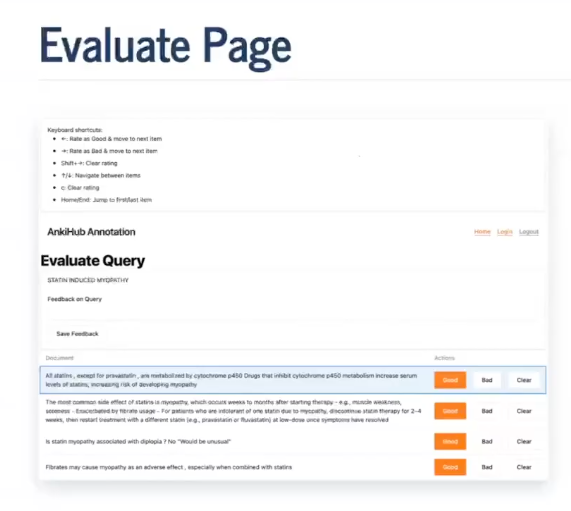

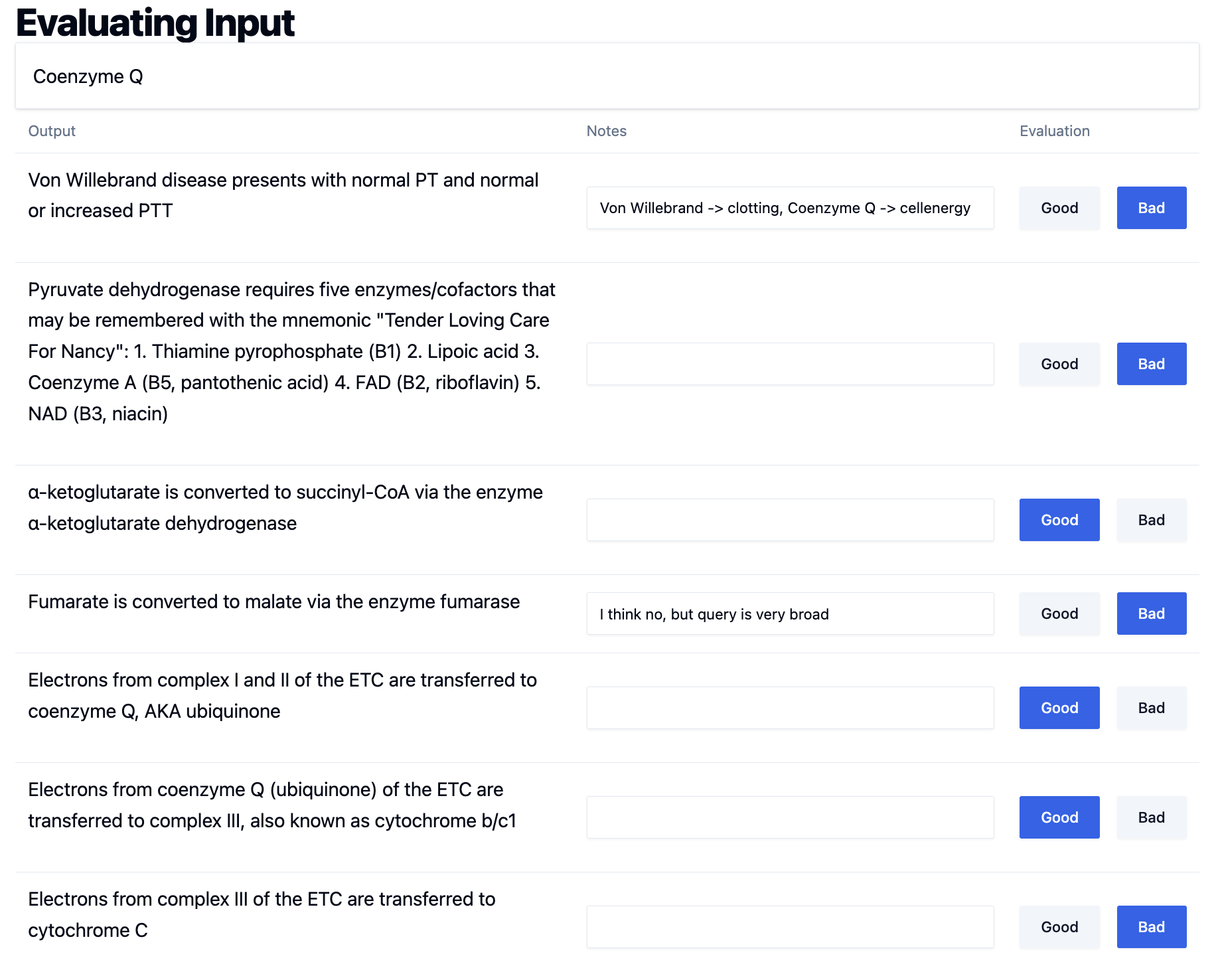

The Evaluation Page: HTMX Integration

The evaluation interface shows where FastHTML with HTMX integration - this is how you provide some of the modern, dynamic website functionality folk expect:

@rt

def evaluate(input_id: str):

documents = list(db.annotations.rows_where('input_id=?', [input_id]))

body = []

for doc in documents:

body.append({

'Output': render_md(doc['document']),

'Notes': Input(

value=doc['notes'],

cls='min-w-96',

name='notes',

hx_post=update_notes.to(input_id=input_id, document_id=doc['document_id']),

hx_trigger='change'

),

'Evaluation': eval_buttons(input_id, doc['document_id'])

})

return Container(

H1("Evaluating Input"),

Card(render_md(documents[0]['input'].replace('\\n', '\n'))),

TableFromDicts(['Output', 'Notes', 'Evaluation'], body)

)

Several useful bits and bobs here:

1. Markdown Rendering: render_md() uses Monster UI’s component that calls mistletoe behind the scenes, then applies Tailwind classes for styling.

2. Tailwind Integration: cls='min-w-96' shows how you can use Tailwind classes when Monster UI doesn’t provide exactly what you need.

3. HTMX Auto-Save: hx_trigger='change' means notes save automatically when users type, without submit buttons. The hx_post attribute calls a Python function that updates the database.

Note that the change event fires when an input field loses focus AND its value has changed - this is different from input events which fire on every keystroke. So users finish typing and tab away, then the save happens automatically.

HTMX: Partial Page Updates

The update_notes shows HTMX’s usefulness:

@rt

def update_notes(input_id: str, document_id: int, notes: str):

record = Annotation(input_id=input_id, document_id=document_id, notes=notes)

db.annotations.update(record)

# No return value - just updates database

When users type in the notes field, HTMX automatically:

- Triggers on the

changeevent - Posts to the

update_notesroute - Updates the database

- Requires no page refresh or JavaScript

So with HTMX you can build interactive interfaces that feel like modern web apps while keeping all logic in Python and server side.

Button State Management

The evaluation buttons show state management being used to control the view:

def eval_buttons(input_id: str, document_id: int = None):

target_id = f"#eval-{input_id}-{document_id}"

_annotation = db.annotations[input_id, document_id]

def create_eval_button(label: str):

return Button(label,

hx_post=evaluate_doc.to(input_id=input_id, document_id=document_id, eval_type=label.lower()),

hx_target=target_id,

cls=ButtonT.primary if _annotation.eval_type == label.lower() else ButtonT.secondary,

submit=False)

return DivLAligned(

create_eval_button("Good"),

create_eval_button("Bad"),

id=target_id[1:]

)

@rt

def evaluate_doc(input_id: str, document_id: int, eval_type: str):

db.annotations.update(Annotation(input_id=input_id, document_id=document_id, eval_type=eval_type))

return eval_buttons(input_id, document_id) # Returns updated buttons

The logic here is:

Each button checks if the database state matches its own label. The Good button asks “Am I the one that’s currently selected?” by comparing _annotation.eval_type with "good". If yes, it shows blue (primary styling). If no, it shows gray (secondary styling). Same logic for the Bad button with "bad". So if a record is marked as “good” in the database, the Good button shows blue and the Bad button shows gray.

When users click “Good” or “Bad”:

- HTMX posts to

evaluate_doc - Database updates with the evaluation

- Function returns new button HTML with updated colors

- HTMX replaces just the button container (via

hx_target) - User sees immediate visual feedback

What makes this work is using hx_target to replace both buttons together rather than just the clicked button. This way both buttons update their styling to reflect the new state - the clicked button becomes primary (blue) and the other becomes secondary (gray). No page refresh, no complex JavaScript state management.

Keyboard Shortcuts

Isaac builds keyboard shortcuts for his data annotation tools.

They’re most valuable when individual tasks are quick. If you’re reviewing 400 flashcards at 2 seconds each, removing mouse navigation saves significant time. If each review takes 5 minutes, keyboard shortcuts matter less.

Phoenix Integration: Clean Data Flow

The annotation system integrates with Phoenix (an AI experiment database) to maintain clean data flow:

Phoenix stores traces, annotations, datasets, experiments, and prompt versioning.

This integration pattern - temporary local storage flowing to permanent experiment storage - keeps the annotation interface uncluttered.