LLM Evals Course Lesson 4: Multi-turn and Collaborative Evaluation

Notes from lesson 4 of Hamel and Shreya's LLM evaluation course - handling multi-turn conversations and building evaluation criteria through collaboration.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 11 min read

The fourth lesson of Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s LLM evaluation course covered two distinct challenges: evaluating multi-turn conversations and building evaluation criteria through collaboration.

Part One: Multi-turn Evaluation Beyond Single Exchanges

Multi-turn evaluation presents unique challenges compared to single-turn interactions. The same analyse-measure-improve lifecycle applies, and binary criteria remain a good starting point. But conversations introduce new dimensions to consider.

What Changes with Multi-turn

When evaluating multi-turn conversations, three aspects come into play that don’t matter as much with individual turns:

-

Context and Memory: Does the AI remember earlier parts of the conversation? How does behaviour change as the conversation lengthens?

-

Consistency: Do responses align across turns without contradictions?

-

Overall Session Goals: Unlike single turn-response pairs, we care whether the entire session achieved the user’s objective.

The “trace” now encompasses the entire multi-turn conversation rather than a single exchange.

Two Levels of Evaluation

When evaluating conversations, you work at two levels of abstraction:

Session Level (recommended starting point):

- Evaluates the entire conversation for goal achievement

- Uses binary pass/fail initially

- For NurtureBoss: A session fails if a prospect wanting a two-bedroom tour ends up with no clear tour options, even if individual responses were polite

Turn Level (for debugging):

- Assesses individual turn-by-turn responses

- Measures quality, relevance, correctness, safety, tone

- Challenging to scale across long conversations

- Used specifically when you’re debugging an overall problem identified at session level

Start at session level and when you identify (through error analysis) a type of problem you need to solve, switch to turn level evaluation to debug specific it.

Practical Strategies for Multi-turn Testing

Collecting Initial Traces: Don’t overthink this. Aim for ~100 conversational traces using the dimensional approach from lesson 2. Remember those three dimensions:

- Features/Intent (what users want to do)

- Caller Status/Persona (who is asking)

- Query Complexity/Scenario (how well-formed the request is)

Have your team simulate different personas and create 10-15 conversations each, systematically covering these dimensions rather than creating random conversations. Just do anything you can to get an initial dataset.

Finding and Fixing Failure Points: As you assess these multi-turn conversations, you’ll discover errors that emerge at specific points in the trace. You need strategies that let you focus on these failure points and iterate on them specifically. There are two approaches depending on whether the issue is truly multi-turn or not.

Isolating Failures: When errors appear partway through a conversation, try reproducing them as single-turn tests. If a shopping bot gives the wrong return policy on turn 4, test with a direct query: “What’s the return policy for product X?” If it’s still wrong, you’ve identified a grounding or retrieval issue, not a multi-turn problem.

Handling True Multi-turn Issues: For problems that genuinely stem from conversation context (forgetting earlier information, confusion between context elements), you basically freeze the conversation at the failure point. If an error only occurs on turn 4 and relates to context handling, snapshot those first four interactions - you’re always kicking off from that fixed starting point for iteration and improvement.

This leverages how LLMs actually work - they don’t innately remember conversations. Instead, a messages array gets sent back with every interaction, holding all previous back-and-forth exchanges. By freezing the messages array at the problem point, you create a consistent baseline for testing improvements. This makes perfect sense when you think about it.

Testing Robustness Through Perturbation: Deliberately modify existing traces to test how your system handles mid-conversation changes. Test both completely different intents (user switches from booking a tour to asking about maintenance) and additional constraints to original intents (halfway through a restaurant recommendation, the user mentions their friend is vegetarian). You kind of just have to test this - there’s no clever way to anticipate how the agent will react to these changes. This “perturbation” testing should be part of your standard approach for building robust multi-turn products.

Performance Degradation: Ensure your test set includes conversations of varying lengths. Performance often drops in longer conversations - the system forgets context, contradicts earlier responses, or loses track of instructions. This degradation over length is something people frequently forget to test.

Automation for Multi-turn: When creating an LLM-as-judge for multi-turn conversations, it evaluates binary criteria on the entire trace. The focus is on overall success/failure of the session rather than turn-by-turn assessment.

Five Key Takeaways for Multi-turn Evaluation

- Start at session level, zoom to turn level only for debugging

- Try to isolate multi-turn failures as single-turn tests to determine if they’re truly multi-turn issues

- For true multi-turn issues, freeze the conversation at the failure point and use that as your iteration baseline

- Deliberately perturb your traces to test system robustness

- Vary conversation lengths in your test set to catch performance degradation

Part Two: Collaborative Evaluation Beyond Individual Judgment

The second half of the lesson addressed a common challenge: evaluation criteria are often subjective, and individual judgment has limitations.

Why Collaborate?

Qualities like helpfulness, tone, creativity, or catchiness get interpreted differently by different people. Everyone has biases and blind spots, and no single expert covers all aspects relevant to understanding user needs.

This is also largely about taste. Whilst having great taste is useful - as it always has been in product - understanding that your taste is a starting point but not the endpoint is important. Collaborative evaluation is a technique to systematically bring in multiple human experts and stakeholders to define what good and bad mean. It’s a technique to mitigate against bias, to broaden the technical expertise on evaluations, and to make sure that your individual taste is a starting point, not the endpoint.

The goal here is actually three things that are worth considering individually:

Defining criteria - Getting clear on what you’re even measuring in the first place

Refining criteria - As you see more examples, your understanding evolves. When I was marking student papers, the way I marked the first paper wasn’t the same as the last - examining dozens of approaches refines what you think good looks like. I’d try to mitigate this by spending time working on a rubric and trying hard to stick to it, but also doing things like randomising - putting all the question ones in a pool and marking them in random order, then doing all the question twos in random order. That way no individual student is penalised or rewarded by being first or last in the cohort. But these techniques didn’t solve the problem, they just mitigated some of the effects. Multiple perspectives help catch and account for this drift.

Applying criteria reliably - Having a group gives you the option to detect differences and focus on them. This helps prevent momentary lapses and ensures consistency.

These three goals - define, refine, apply - are what collaborative evaluation is trying to achieve.

The Friction Trade-off

Hamel introduces the concept of “benevolent dictators” - principal domain experts who make final calls on evaluation criteria. His point is around practicality primarily: complexity increases exponentially with every person added to the annotation process.

He estimates 75% of teams should probably use the benevolent dictator model, even in large companies, because they’re likely working on product slices that aren’t that complex.

My view is slightly different: I think it’s basically a trade-off. Both things are true - if you have the benevolent dictator model, you’re going to be more efficient and quicker, but you won’t have all perspectives captured. More friction is worth it when diverse perspectives have high value (extremely diverse user base) or there’s little margin for error. For most cases, having a single decision-maker is better than - and it’s probably fine for most cases, just like Hamel says.

But this is really an issue of taste and a product decision about trade-offs rather than purely an evaluation methodology question.

The sweet spot is probably a principal domain expert who is empowered and influential, but maybe isn’t the final word, with other perspectives balanced by the product lead. You basically need someone empowered to make decisions but not operating in a vacuum.

The Collaborative Workflow

The workflow is very reminiscent of social sciences methods - grounded theory, having multiple coders. It’s all very much like good practice from social sciences, just being applied to AI evaluation:

- Assemble Team: 2+ annotators with relevant expertise/stakeholder views

- Draft Initial Rubric: Define criteria (e.g., “Is email tone appropriate?”) with initial pass/fail examples. You’ll probably do multiple criteria at once.

- Select Shared Annotation Set: 20-50 diverse traces, including edge cases (though they sometimes say up to 100)

- Independent Annotation: Everyone labels traces without discussion - this is crucial because it surfaces rubric ambiguities

- Measure Inter-Annotator Agreement: Quantify consistency using Cohen’s Kappa

- Alignment Sessions: Discuss disagreements to refine the rubric (not just to get the “right” label)

- Revise & Iterate: Update rubric, relabel, remeasure until Kappa ≥ 0.6

- Finalise Rubric & Gold Labels: Document the refined rubric and create consensus-labelled dataset

Points 6 through 8 are the most important part, and these are the points I think most people are going to skip: disagreements aren’t just opportunities to get the “right” label. They’re opportunities to refine your rubric. If two annotators with the same rubric reach different conclusions, the rubric itself is probably ambiguous or subjective.

Understanding Cohen’s Kappa

The workflow mentions using Kappa ≥ 0.6 as an indication of “good enough” agreement, but it might not be obvious to everyone what that actually means.

Raw agreement percentages can be misleading. If 90% of your traces are “pass” and only 10% are “fail,” random annotators would agree ~82% of the time just by chance. An 85% observed agreement might seem good, but the Kappa would only be ~0.17, revealing the agreement is mostly luck.

In contrast, with balanced 50/50 pass/fail classes, chance agreement would be 50%. That same 85% observed agreement would yield a Kappa of ~0.70, showing substantial real agreement beyond chance.

The interpretation scale (Landis & Koch, 1977):

- < 0: Poor

- 0.21-0.40: Fair

- 0.61-0.80: Substantial

- 0.81-1.00: Almost Perfect

Aim for Kappa ≥ 0.6 for reliable labels.

Refining the Rubric

When disagreements arise, the goal is to improve the rubric for future consistency. Strategies include:

Clarifying Definitions: Turn vague criteria like “handles ambiguity well” into concrete requirements like “asks at least one clarifying question.”

Adding Illustrative Examples: Include examples of good copy from your content team to guide evaluators who aren’t content experts.

Adding Decision Rules: Specify exactly how the system should handle tricky situations.

Splitting Criteria: Sometimes disagreements reveal that people are focusing on different aspects of the same criterion. “Helpfulness” might need splitting into “factual relevance” and “proactivity.” This is why collaborative workflows are actually very useful - they reveal when a single criterion is trying to do two things at once.

This reminds me of Edward Tufte’s principle from Envisioning Information (which I used when teaching UX design):

To clarify, add detail. Clutter and overload are not attributes of information, they are failures of design. If the information is in chaos, don’t start throwing out information, instead fix the design.

Apparent complexity often comes from vagueness. Adding the right specific details actually makes things simpler.

The Value of the Process

What you actually get from this collaborative process:

- A refined rubric that’s clear and unambiguous enough for anyone to apply consistently - this is often underemphasised but it’s incredibly valuable

- Gold labels - high-confidence ground truth validated by multiple experts, which become your reference standards for training LLM judges and onboarding new team members

Interestingly, LLMs can help refine rubrics. After you’ve identified disagreements and made judgments about them, you can feed all this information to an LLM to propose rubric changes. But the human expertise and judgment must come first - the LLM is just a tool to help synthesise what you’ve learned.

Why Product Perspective Matters in Evaluation

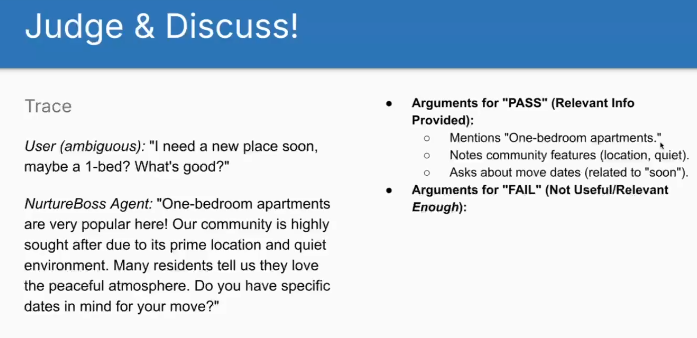

A good example from the lesson demonstrated why domain expertise matters in evaluation. When asked about one-bedroom apartments, the NurtureBoss bot provided a generic response mentioning “peaceful atmosphere” and “prime location.”

The scenario here would be two separate evaluators annotating the same LLM output. A developer might annotate this as a pass - it’s technically correct, mentions one-bedrooms, and asks about move-in dates. But a product manager would fail it immediately.

The distinction is where product taste comes in: this system is meant to drive sales. Generic copy that could describe any property doesn’t convert prospects. Effective responses need specific property information, compelling details, and concrete value propositions. A response about “peaceful atmosphere” tells prospects nothing they couldn’t assume about dozens of other properties.

This illustrates why you shouldn’t outsource annotation to people without domain expertise. An LLM judge trained without this product perspective would miss what makes a response actually useful for the business. The technical accuracy that satisfies a developer’s criteria can be entirely inadequate for achieving business objectives.

thingsithinkithink

-

Perturbation testing is nice - I have struggled to frame the problem of detecting a directional shift in user intent - and I haven’t really wrangled with it enough to feel comfortable - I think this will help.

-

Criteria drift is real and consistently underacknowledged in my experience. Every complex evaluation task I’ve done has involved my standards evolving as I see more examples. .