LLM Evals Course Lesson 5: How to Evaluate Complex Architectures

Notes from lesson 5 of Hamel and Shreya's LLM evaluation course - evaluating retrieval quality, generation quality, and common pitfalls in RAG systems.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 13 min read

The fifth lesson of Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s LLM evaluation course moved into evaluating more complex systems. Previous lessons focused on single-step evaluation, but this session addressed RAG systems, tool calling, and other architectures that introduce additional components to evaluate.

We’re still in the analyse-measure phase of the evaluation lifecycle. The focus remains on understanding issues and identifying failure modes rather than implementing improvements.

RAG Isn’t Dead

The early post-ChatGPT period saw considerable attention on RAG implementation details - chunking strategies, vector databases, embedding models. Whilst these details matter, they became the single greatest focus when they’re just one part of a larger system.

Some claim RAG is dead, but this misunderstands what RAG actually is. If you think of RAG narrowly as similarity search between vector embeddings, you might believe it’s being superseded. But if you understand RAG as the retrieval stage that grounds LLM outputs in external knowledge, it’s clear this capability remains fundamental.

Shreya and Hamel position RAG correctly: it’s how you connect LLMs to broader context beyond their training data.

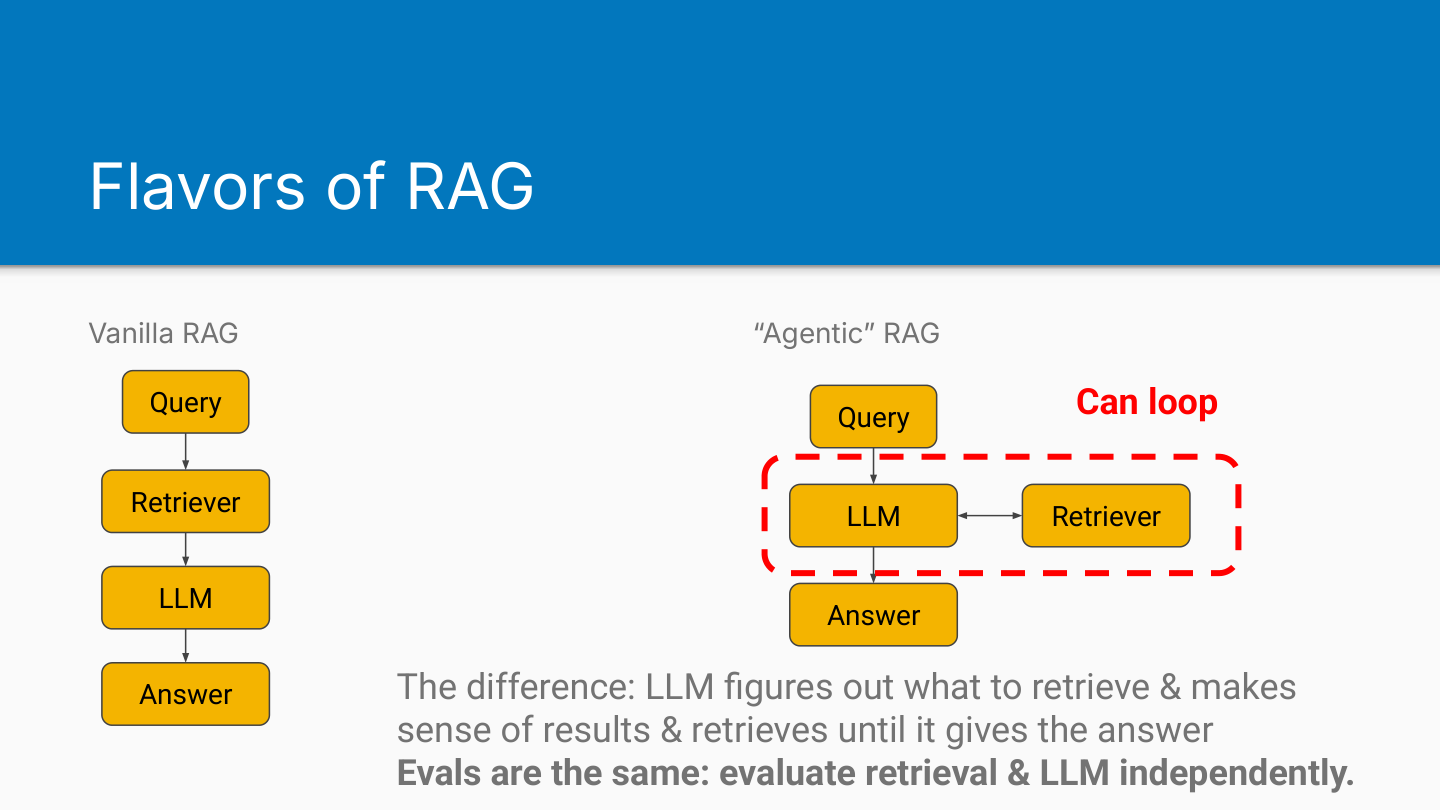

The field is moving from vanilla RAG (single semantic search retrieval step feeding directly to generation) through hybrid search (involving semantic search plus BM25), to agentic RAG.

Agentic RAG isn’t fundamentally different from vanilla RAG. Both have retrieval and generation components. Agentic RAG just allows multiple retrieval steps with the LLM orchestrator deciding when and how to retrieve additional context.

Was the Right Context Found?

Evaluating retrieval quality boils down to one question: is the right context available to the LLM?

Your evaluation dataset needs queries paired with the relevant document chunks that should be retrieved for those queries. A “chunk” here is simply whatever your retrieval process returns - typically a unit of text from your knowledge base, but it could be a full document, an image, or any other retrievable unit.

Creating Synthetic Evaluation Data

Shreya presents a straightforward process for building this evaluation dataset:

- Start with your document chunks

- For each chunk, identify a salient fact a user might want to know

- Generate a realistic question that can only be answered by that fact

- You now have a query-chunk pair for evaluation

This works backwards from typical retrieval: normally users ask questions and you find chunks. For evaluation data, you start with chunks and create questions. Later you test whether your retrieval system can find that chunk given the question.

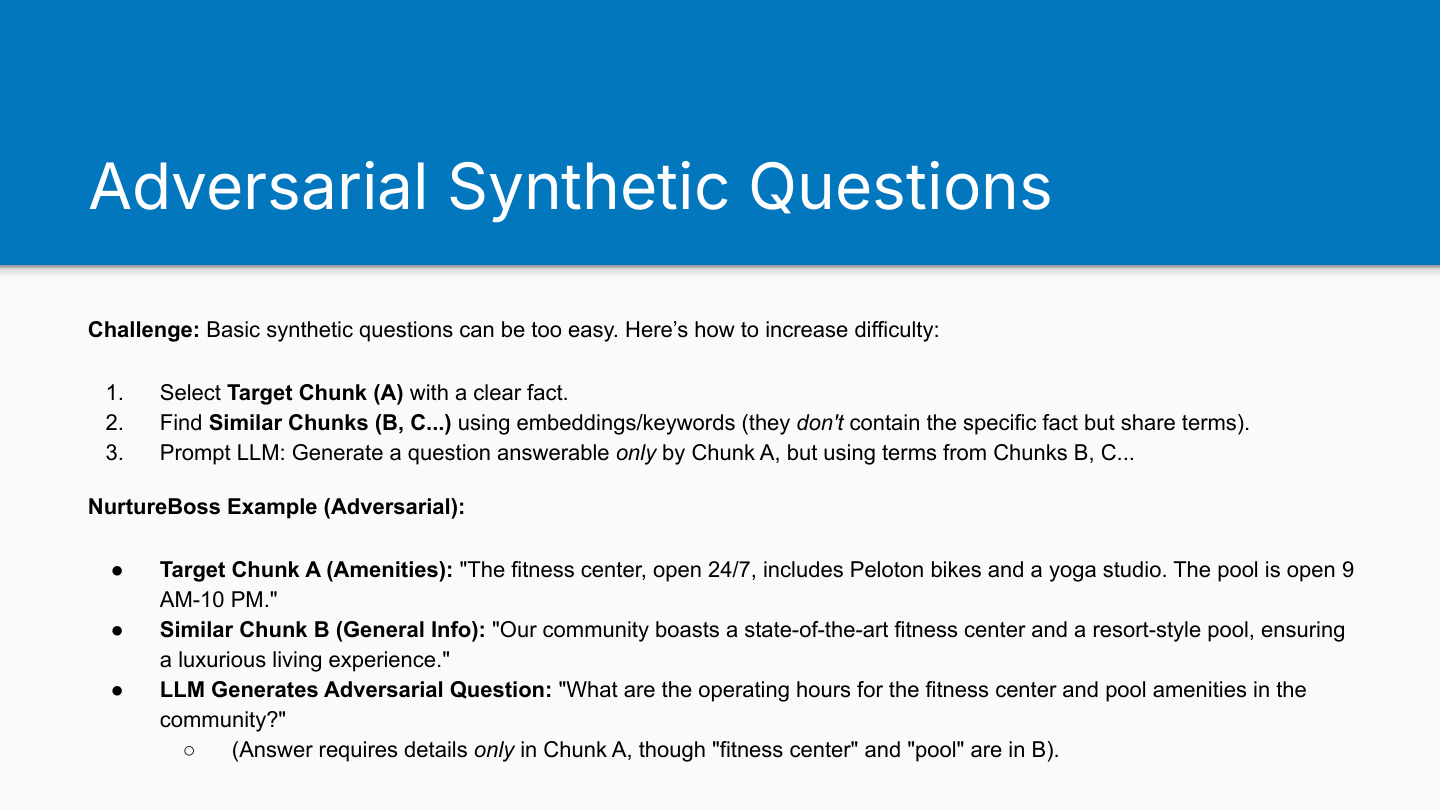

Creating Adversarial Test Cases

The basic approach doesn’t capture everything. Users ask questions requiring information from multiple chunks. Sometimes multiple chunks could answer a query, making evaluation less straightforward.

You can create adversarial synthetic questions that stress-test your retrieval:

- Find chunk A with a clear fact

- Find similar chunks B and C with related terms but not the fact

- Generate a question answerable only by chunk A but using terminology from B and C

- If your retriever returns B and C instead of A, it failed

This creates a trap where term matching would retrieve the wrong chunks.

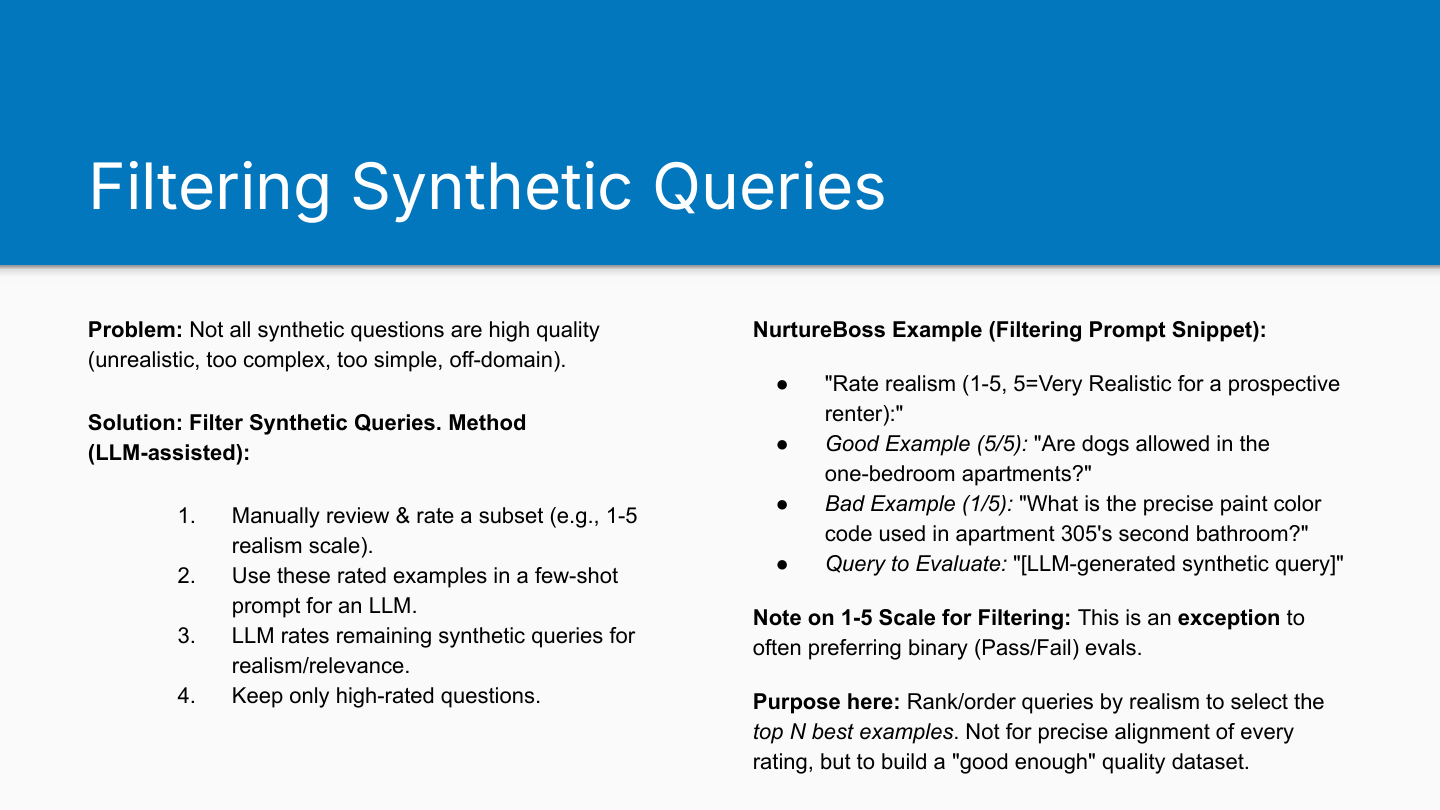

Filtering Synthetic Queries

Not all synthetic questions are high quality. They might be unrealistic, too complex, too simple, or off-domain.

Shreya’s filtering process:

- Manually review and rate a subset (1-5 realism scale)

- Use rated examples as few-shot prompts for an LLM

- LLM rates remaining synthetic queries

- Keep only high-quality queries (3+ rating)

She uses a 1-5 Likert scale here despite advising against such scales elsewhere in the course. The distinction matters: this isn’t measuring failure mode prevalence in your system or evaluating LLM output quality. You’re simply filtering to get approximately good synthetic queries to start your evaluation. The fuzziness of a 1-5 scale works for ranking queries from most to least realistic. Rather than trying to achieve perfect precision, you’re only trying to create a useful starting dataset. This is why it’s not such a big deal that we’re using a 1-5 scale - the LLM doesn’t need to be perfect.

Tips for Synthetic Data Creation

Seed with realism: Use real user queries as few-shot examples in your generation prompts.

Data first, retrieval later: Generate synthetic data independent of your retrieval method. Don’t anticipate whether you’ll use BM25 versus semantic search. If you build retrieval first, you’ll bias your examples toward what you expect to work and miss holes in your system.

Include complexity: Create queries requiring multi-hop reasoning across multiple chunks when users will ask such questions.

Retrieval Metrics

Once you have evaluation data, you need metrics for measuring retrieval quality. The course covers four metrics focusing on the ranking of retrieved chunks.

Recall@K: The Most Important Metric

Recall@K measures coverage of all relevant chunks for a query, how many appear in your top K results?

This is the most important metric for RAG. Your LLM can only answer correctly if the right context appears somewhere in the retrieved chunks. It doesn’t matter if irrelevant chunks are present - what matters is whether the correct information made it through retrieval.

This is how I evaluated the FCDO LLM product. The retrieved chunk didn’t need to be top-ranked. Irrelevant chunks didn’t disqualify the result. Success simply meant the correct answer appeared somewhere in the K documents returned.

Precision@K: Managing Red Herrings

Precision@K asks - of the K chunks retrieved, how many were actually relevant?

This measures the accuracy within your retrieval window. You’re looking for “red herrings” - irrelevant context that made it through retrieval.

Early in the FCDO project, we had only 4,000 tokens in GPT-3.5’s context window. We later got a boost to 16K tokens. These context windows seem shockingly small now. With modern long-context models, precision matters less than it used to because you have context to spare.

However, irrelevant context can still distract the LLM from correct information, potentially degrading answer quality.

Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR): Position Matters

When queries have multiple relevant chunks or precision particularly matters for your LLM, MRR becomes useful.

MRR measures how high up in the ranking the first relevant chunk appears.

Calculate it as the average of 1/rank for the first relevant document across all queries. If the first relevant document is in position 1, the score is 1.0. In position 2, the score is 0.5. The score decreases as the first correct document appears later.

This matters for two reasons:

- When only one factoid document is needed, you want to avoid wasting LLM attention on dead ends

- LLMs perform better when appropriate context appears earlier in the window

Despite “needle in a haystack” benchmarks suggesting otherwise, LLMs suffer from “lost in the middle” problems. They pay more attention to the beginning and end of context windows than the middle. When possible, place relevant documents at the top or bottom rather than randomly distributed.

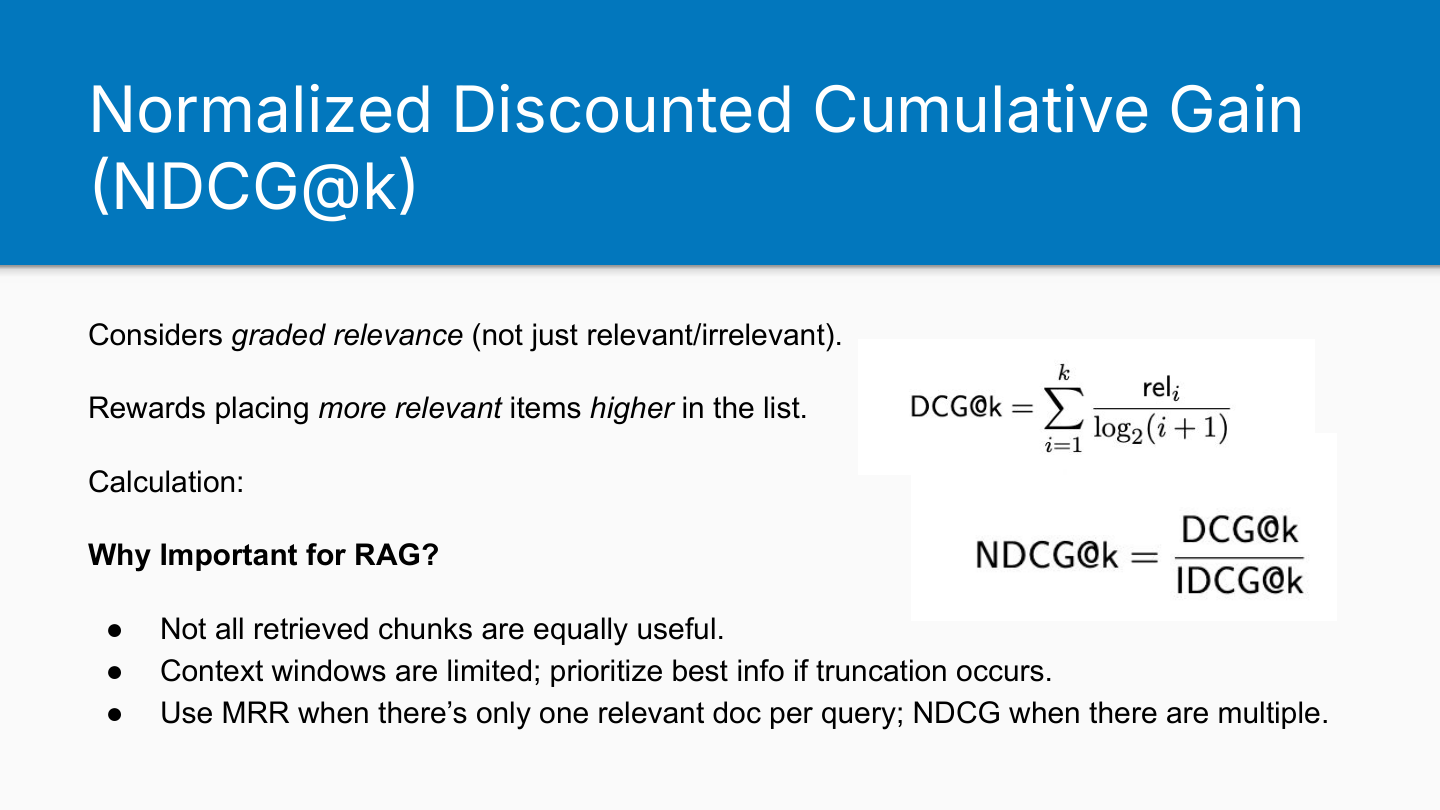

Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG@K): Graded Relevance

NDCG@K extends MRR by understanding that:

- Multiple chunks may be relevant to a query

- Not all relevant chunks are equally useful

- More relevant items should rank higher

This rewards placing the most relevant chunks at the top of your ranking.

You don’t need NDCG@K if you’re using binary relevance (relevant/not relevant). You need it when:

-

Grading relevance on a scale: Some chunks are more relevant than others. For example, an API reference document explaining a function is more relevant than a blog post discussing the same function, even though both contain the correct answer.

-

Multiple relevant chunks per query: When several chunks could answer the query but with varying quality, NDCG@K helps measure whether you’re surfacing the best ones first.

MRR works best when there’s just one relevant document per query. NDCG@K shines when queries have multiple relevant chunks with varying degrees of relevance.

Evaluating Generation Quality

All the metrics above tell us how to evaluate retrieval, but we’re not specifically trying to achieve good retrieval metrics for their own sake. We’re trying to build systems using LLMs. So knowing when, where, and how to apply these methods is actually quite important.

Once you can measure retrieval quality, evaluating your end-to-end RAG system becomes straightforward. Apply error analysis to queries that retrieved well versus those that retrieved poorly.

Consider a query decomposition stage - common because users often provide long paragraphs containing multiple separate queries. Your system performs better by splitting these into subqueries.

You might find through error analysis that decomposition itself works well, but the way your system phrases decomposed queries produces poor retrieval. The fix belongs in the decomposition stage, not retrieval. You need retrieval metrics to identify this pattern.

The course references the ARES framework (Saad-Falcon et al., NAACL 2024) for generation evaluation, focusing on two dimensions:

Faithfulness

Does the generated answer accurately reflect retrieved context?

Don’t consider faithfulness in isolation - always frame it in your system’s context. Three failure modes:

- Hallucinations: Information in the answer that doesn’t appear in retrieved context. You want the LLM grounded in your data store, not its training data.

- Omissions: Key information from retrieved context missing in the generated output.

- Misinterpretations: Context present in the window but used incorrectly in the answer.

Relevance

Is the faithful answer actually relevant to the original query?

An answer can be perfectly faithful to retrieved context whilst failing to address what the user actually asked.

Common Pitfalls

Shreya and Hamel both shared common pitfalls from their experience.

Shreya’s Pitfalls

Over-reliance on End-to-End Metrics

Skipping systematic retrieval evaluation and jumping straight to holistic end-to-end evaluation inevitably forces you back to examine retrieval anyway. Start with retrieval evaluation first.

Over-fitting to Synthetic Datasets

Synthetic queries can miss real user query patterns - underspecified requests, typos, unusual phrasing. Ensure your synthetic data reflects actual user behaviour.

Wrong Metric Choice

Understanding when to use recall versus precision versus MRR versus NDCG@K matters. The wrong metric obscures what’s actually happening in your system.

Ignoring Chunking Strategy Impact

Don’t blindly split documents into fixed-size chunks (like 3-sentence chunks) without considering whether that granularity matches what users need.

One approach: take real user queries, manually find relevant information in documents, compute average chunk size based on those queries. Use this to inform your chunking strategy for the entire corpus.

Not Checking Generation Grounding

Failing to verify that your LLM actually uses retrieved documents correctly - the “G” part of RAG.

Hamel’s Pitfalls

Verify RAG is the problem: During error analysis, confirm your system is actually failing due to retrieval before investing heavily in RAG evaluation. If retrieval works fine, focus elsewhere.

Don’t default to vector databases: People assume vector databases are the only retrieval method. Stay open-minded. Hamel has seen cases where showing an LLM a hierarchical table of contents and asking which sections seem relevant worked better than semantic search. Claude Code uses traditional developer search tools (grep, find) effectively. Consider giving your LLM access to your existing search system - it’s often easier to debug because you already understand how it works.

Understand your product: Choices like “what is K?” depend on how your product works. How many documents are shown to users? At what stage? How important is precision versus recall? This informs your target metrics and helps stakeholders understand the precision-recall trade-off. You can achieve 100% recall by retrieving everything, but precision suffers.

Do data analysis: When queries have poor metrics, investigate why. Are short queries performing better than long ones? Do certain query types struggle? Look for patterns in good versus bad queries. You’ll often find engineering bugs this way. Apply error analysis principles - it’s rapid experimentation that builds intuition quickly.

Don’t waste time bike-shedding tools: The first response to poor RAG performance shouldn’t be trying a new vector database or chunking strategy. Let error analysis drive these decisions. Have data showing your chunking isn’t working before changing it.

Tool Calling and Agentic Systems

Beyond RAG, modern LLM applications increasingly use tool calling. Agentic systems - where LLMs plan, make sequences of decisions, and loop rather than following fixed left-to-right workflows - rely fundamentally on tool use.

The basic evaluation lifecycle (analyse, measure, improve) still applies, but tool calling introduces distinct evaluation challenges.

The Tool Calling Process

Tool calling involves three stages:

- Tool selection: The LLM chooses which tool to use from a predefined list

- Argument generation: The LLM generates arguments for the chosen tool

- Execution and processing: The system executes the tool and the LLM processes the output

The first step depends entirely on how well you’ve described your tools. LLMs rely heavily on the names, descriptions, and parameter specifications you provide. Ambiguous descriptions or multiple tools with similar names lead to poor tool selection.

When building MCP tools, I had added handwritten MCP tools for allowing Claude to speak to GPT-5 and for allowing Claude to speak to Gemini. My first naive attempt used the same tool name for both AI bots. I realized this was causing confusion for the LLM. This is a lesson I learned quite quickly. I think namespace clashes will be a big problem with MCPs.

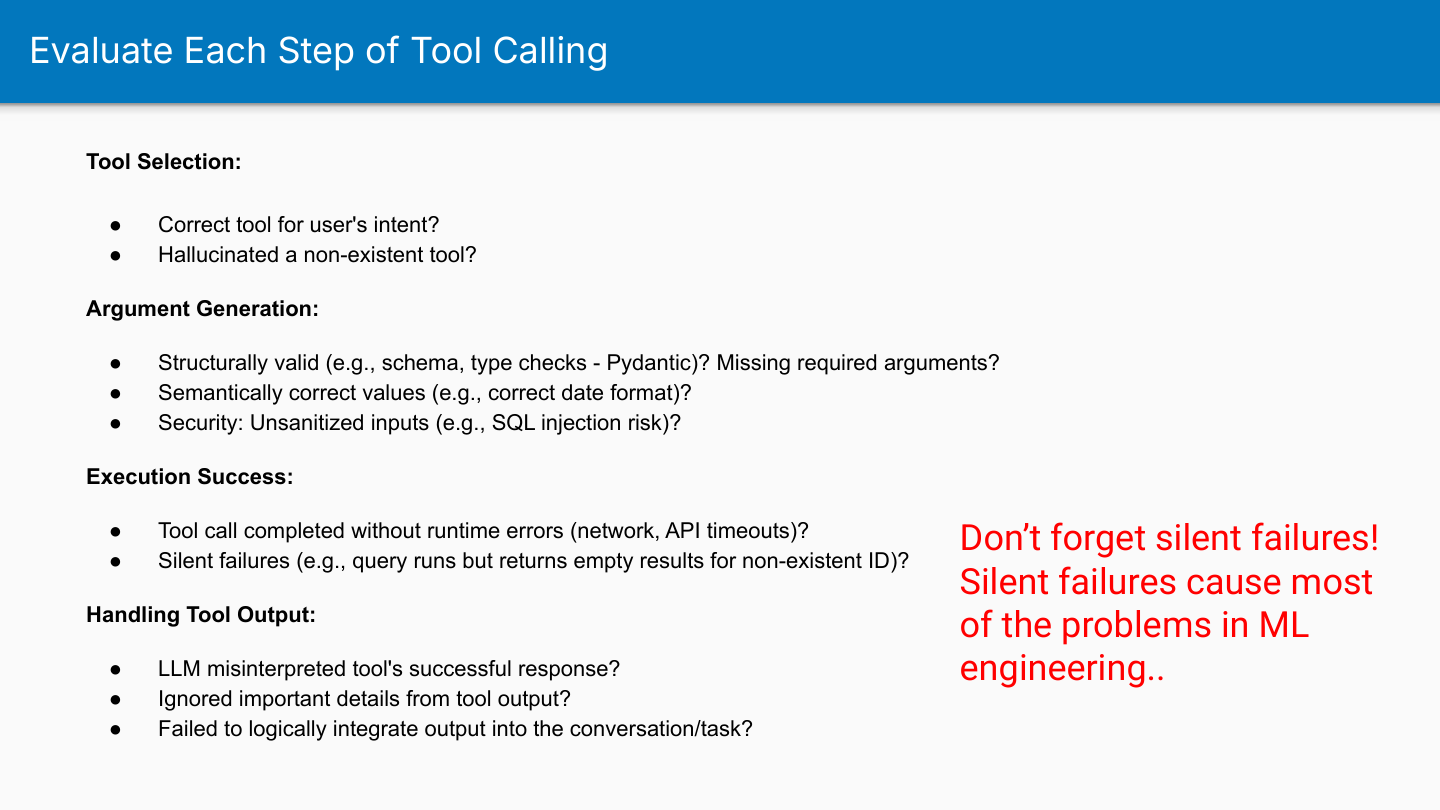

Evaluating Each Stage

Tool Selection

Start with the most basic question: did the LLM choose the correct tool for the user’s intent?

With good ground truth data, you don’t need LLMs to evaluate this - use computational methods. Check whether:

- The correct tool was selected

- The LLM hallucinated a non-existent tool (this commonly appears during error analysis)

Argument Generation

Multiple levels of correctness apply here:

Structural validity:

- Does the output match the expected schema?

- Are types correct?

- Are required arguments present?

Value correctness:

- Are the actual values appropriate?

- Common failure: date formatting issues - wrong format, returning a list of individual dates instead of a range, or multiple sub-ranges instead of the requested single range

Security:

- Are inputs sanitised?

- SQL generation particularly needs checking for injection risks

Execution Success

Assuming structurally valid arguments, did the tool actually complete without runtime errors?

Watch for silent failures - the execution didn’t error but returned empty or meaningless results. This parallels traditional ML engineering where NaN values or null features cause pipelines to “succeed” whilst producing garbage output.

Examples:

- API calls failing due to network issues returning 500 errors

- Text-to-SQL queries returning empty tables

Output Processing

The LLM must handle tool responses appropriately:

- Did it correctly interpret successful responses?

- Did it ignore important details from the output?

- Did it logically integrate the output into the conversation or task?

A common failure in text-to-SQL: the query returns an empty table, but the LLM responds “thanks, great!” and hallucinates an answer not present in the results.

The Connection to ML Engineering

Shreya emphasised that silent failures were one of the biggest causes of problems in traditional ML engineering. The same mindset applies to agentic systems: inspect data flow throughout your agent trace and verify each stage produces sensible output.

Tool calling shares characteristics with RAG - a tool is fundamentally a way to retrieve information or perform actions, just like RAG retrieves documents. Both require checking:

- Was the right thing retrieved/called?

- Were the arguments/queries appropriate?

- Did execution succeed?

- Was the output used correctly?

thingsithinkithink

- I think that MCP name clashes is going to become a problem actually, as suggested by Shreya. When building MCP tools, I had added handwritten MCP tools for allowing Claude to speak to GPT-5 and for allowing Claude to speak to Gemini. My first naive attempt used the same tool name for both AI bots. I realized this was causing confusion for the LLM. This is a lesson I learned quite quickly. I think namespace clashes will be a big problem with MCPs.

- Tags:

- Llm

- Evaluation

- Rag

- Retrieval

- Course-Notes