Hamel & Shreya's LLM Evals Course: Lesson 1

Notes from the first lesson of Parlance Lab's Maven course on evaluating LLM applications - covering the Three Gulfs model and why eval is where most people get stuck.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 11 min read

I’ve started taking Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s course on evaluating LLM applications. The course attracted over 700 students from more than 300 companies, which gives you a sense of how much demand there is for systematic approaches to improving AI-driven products. As someone who has taught classes with a maximum of 120 students, I’m glad it’s not me having to monitor the lesson chat.

I’m writing these notes here for myself as a way to come back and check what I learned from the course.

The core premise of the course strikes me as valuable: there are loads of tutorials on building basic AI applications/RAG applications/agents etc. But so many folk get stuck when they’re trying to make their AI system better or go from POC to product. The course is hoping to tell us how do you iteratively improve your product systematically rather than just doing random things and hoping for the best.

The Problem with Current AI Development

Shreya opened with the observation that eval is where most people get stuck in developing LLM applications. There are countless tutorials showing you how to glue together APIs and use different tools, but where people struggle is understanding how to make their AI better - and specifically, how to iterate with confidence that they’re making improvements rather than just guessing.

In every LLM project I’ve worked on, I’ve had to develop custom ways of understanding how the system performs. Generic benchmarks like Humanity’s Last Exam or LLM Arena don’t capture what matters for specific applications. In fact, they’re quite distracting. I’ve been on projects where other members of the team propose using standard eval metrics. It’s easy to lose an argument when there is a standard benchmark on the table, but I don’t find them useful at all for any given project I’m working on. The gap between these academic benchmarks and real world specific use case performance is huge.

What I Care About When I Use LLMs

I rely on a mix of ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, each for different tasks, and my usage patterns tell me that I don’t care about standard benchmarks that much.

I have a lot of understanding about how to control ChatGPT and to get it to do specific things for me. For example, I use it sometimes for data analysis pipelines. I’ll upload spreadsheets and have it compare datasets, write Python code that it runs in its own environment to extract details. I like reading the reasoning traces and then the rest of that paragraph as you’ve got it. The ability to see how the AI arrived at conclusions helps me trust the outputs - though I always verify anything important.

I use Claude mostly as an editor for my writing. I find ChatGPT’s writing style absolutely rubbish. So when I’m using AI to help me with a writing task, I typically work in Claude, iterating back and forth with the shared artifact to create the final text. I spend considerable time dictating to Claude, having it create edited transcripts, then co-creating the actual output. This way I get AI’s ability to pull together different threads whilst ensuring the final result doesn’t sound like AI wrote it (because AI didn’t write it, AI helped me edit it).

I use Gemini for its enormous context length and factual approach to communication. For example, I have a Python program that can recursively work through my Notion notes and combine them into one large text file. I can paste that single text file into Gemini if I need fact checking or if I want to tease out quotes or supporting arguments from my accumulated notes for some point I’m looking to make on a project.

This usage pattern really gets at that point about the difference between benchmarks and what actually matters for various use cases. And that’s basically why I’m looking forward to the course, because I really believe in what the course is stating, that the criteria we care about for any given LLM-based application are not the criteria that we care about with these academic benchmarks. It’s about nuanced, often implicit factors like trustworthy reasoning traces, writing quality, whether the outputs correspond to certain taste preferences and so on. And relying on standard benchmarks just ain’t going to cut it. So I’m really looking forward to learning some best practice from the course.

The Three Gulfs Model

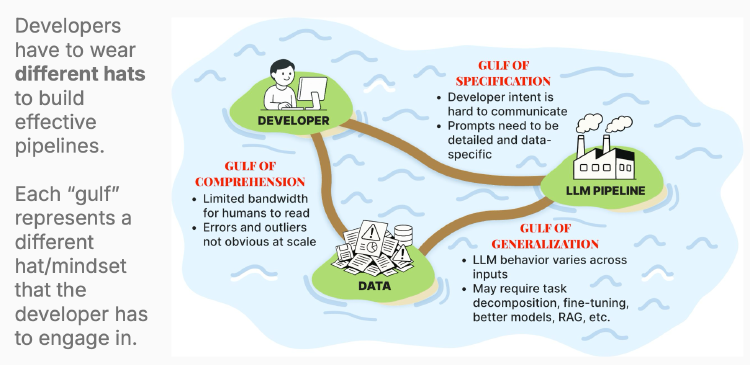

The core of the first lesson was Shreya’s “Three Gulfs Model” for understanding LLM development challenges. She framed this as the different hats developers must wear when building effective pipelines. It’s clear that we’re going to come back to this model throughout the rest of the course as we tackle each of the gulfs.

![Three Gulfs Model diagram showing Developer, LLM Pipeline, and Data nodes with the gulfs between them]

Gulf of Specification (Developer ↔ LLM Pipeline)

This represents the challenge of communicating your intent to the LLM. Getting a great output once is relatively easy; crafting a prompt that consistently produces high-quality outputs is extraordinarily difficult, especially as applications grow more sophisticated.

Shreya emphasised how hard communication actually is. She pointed to the leaked system prompts from major AI assistants - they’re remarkably long because the providers understand the direct correlation between specification quality and performance. Given that every token costs money at scale, the fact that these companies use such extensive prompts demonstrates the relationship between specification and success.

The example she used was asking a recipe bot for “something easy to cook.” What does “easy” mean? Fewer ingredients? Less time? Fewer steps? Equipment requirements? All of these need specifying in the prompt, or you need massive datasets to train on.

This resonates with Ethan Mollick’s observation that the skills required for effective AI use are fundamentally managerial: communication, clarity of specification, knowing what good looks like. These aren’t traditional developer strengths (sorry developers, I know some of you are great at this - but it’s not what we think of as the core dev skills). Having spent a decade teaching game design and software engineering, I learned communication by doing it with students - the immediate feedback cycle of saying something, seeing a student’s eyes glaze over and trying a different tack - or having loads of questions after explaining an idea - that kind of feedback shows you when you’re not communicating well and over time (if you pay attention and try) you get better at it. With LLMs, that feedback loop is much more opaque. It’s much harder to know that you have sufficiently communicated what you want.

Gulf of Comprehension (Developer ↔ Data)

This gulf addresses the bandwidth challenge: you cannot manually review every input and output. You’ve got too much data, and there will be errors and outliers that are hard to spot at scale.

The data encompasses everything: initial problem understanding data, user-generated content that doesn’t match your expectations, and system outputs you’re trying to evaluate. As Shreya noted, “you can’t vibe check your way to understanding what’s going on.”

Hamel shared an anecdote about an apartment leasing AI assistant where the client was convinced the system worked well based on limited testing. Only through systematic data analysis did they identify failure modes around appointment setting, date handling, and other issues that were invisible during casual evaluation.

Gulf of Generalisation (Data ↔ LLM Pipeline)

Even with perfect specification, LLMs aren’t humans. They’re limited by capabilities and context windows, and their performance varies across inputs. This gulf requires understanding model capabilities, task decomposition, fine-tuning, RAG systems, and other architectural decisions.

Shreya’s insight here is that this goes beyond communication clarity. Even if you specify everything as well as any human would require, you still need mechanisms to help the LLM succeed across diverse inputs. This might mean RAG for context limitations, decomposition for complex tasks, or fine-tuning for capability gaps.

In my largest LLM project, I spent considerable time on decomposition - trying to identify the top three problems in user submissions whilst knowing when to break out of rigid approaches. If someone reports being stabbed in the street, you can’t stick to a “find three questions” framework. The LLM couldn’t handle this nuance without significant architectural support.

The Evaluation Lifecycle: Analyse, Measure, Improve

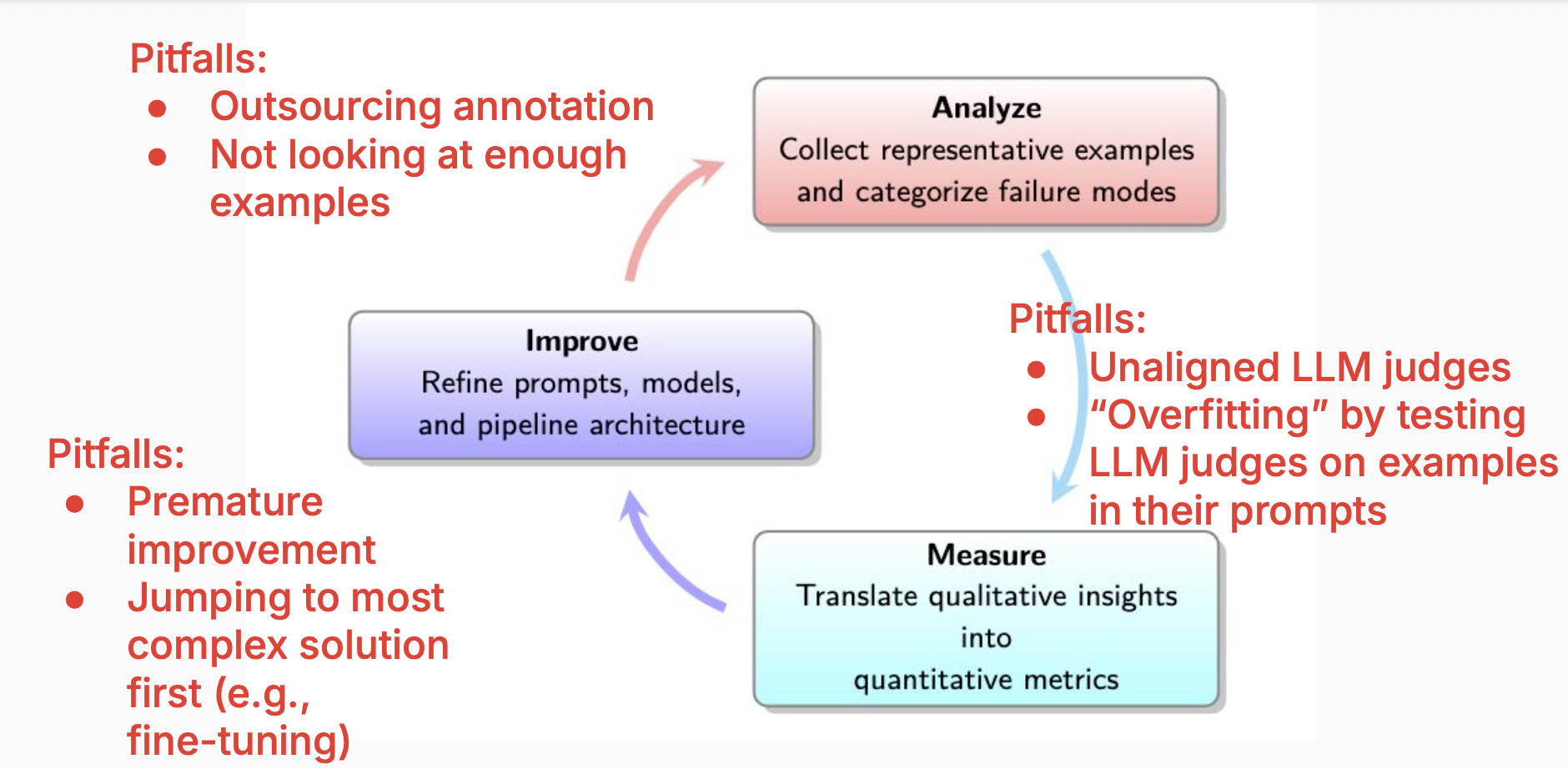

The course proposes a three-stage lifecycle for systematic improvement:

Analyse

Collect representative examples and categorise failure modes. You must look at your data until you reach “theoretical saturation” - the point where reviewing additional examples reveals no new failure modes.

Common pitfalls include outsourcing annotation (never do this - it must be done by domain experts) and not looking at enough examples (minimum 30, aim for at least 50, sometimes 100).

Measure

Translate qualitative insights into quantitative metrics. This involves implementing automated evaluators, including LLM-as-judge approaches, whilst avoiding the trap of unaligned judges or overfitting. I have been quite sceptical of LLM as a judge, thinking of it as the best of a bunch of bad options. Hamel and Shreya have hinted at some more robust approaches when they spoke about error analysis previously, and I’m looking forward to having a better understanding of how good we can make these.

Improve

Refine prompts, models, and pipeline architecture based on insights. The crucial point: avoid premature improvement and jumping to complex solutions first. Don’t fine-tune before exhausting simpler methods.

Recipe Bot: The Course Project

To ground these concepts, the course uses a recipe bot that suggests recipes based on user requests (ingredients, dietary preferences, cooking time). This application can scale from simple to complex, incorporating RAG, multimodal capabilities, or agentic internet search.

We can understand the problems we might face, viewing the recipe bot through the lens of each of the gulfs:

- Comprehension: Understanding diverse queries from “What can I make with these ingredients?” to “How do I create an amazing dessert for my party?”

- Specification: Defining what “easy to cook” means in precise, unambiguous terms

- Generalisation: Ensuring consistent performance across varied inputs even with clear prompts

Prompting Fundamentals and Component Analysis

Shreya recommended considering these as essential prompting components:

- Role and Objective: Define the LLM’s persona (“You are a helpful recipe assistant”)

- Instructions/Response Rules: Clear directives with always/never guidelines

- Context: Relevant background (dietary restrictions, skill level)

- Examples: Few-shot prompting demonstrating desired format

- Reasoning Steps: Chain-of-thought for complex requests

- Output Formatting: Structured responses (JSON, XML tags)

- Delimiters: Clear section separation

I’ve given workshops on how to prompt LLMs to a general audience for ChatGPT and to developers for GitHub Copilot. At some point, I need to put mine online and contrast them with these, but these seem quite reasonable to me.

The iterative nature of prompting was emphasised - finding the perfect prompt is rare and probably the result of a lot of hard work. Your first attempt is a starting point for refinement.

Defining Good vs Bad: Starting with User Unhappiness

Tying back to the way we opened this post, talking about how academic benchmarks are kind of useless and what good looks like really depends a lot on what we’re trying to do. Shreya basically tried to figure out how can we go about understanding what good looks like in the context of our application. Rather than trying to define “good” directly, Shreya suggested starting with potential user unhappiness:

- Ingredients not commonly available

- Ignoring dietary restrictions or allergies

- Unclear instructions

- Inappropriate complexity for skill level

- Unhealthy suggestions when healthy was requested

This “unhappy paths” approach helps define what good isn’t - and the inverse provides a foundation for positive specifications.

LLM Agency Levels

Shreya introduced the concept of LLM agency in a way that I haven’t seen anybody frame it before, i.e. how much freedom the bot has to interpret user wants.

Using the example “I want a quick dinner using chicken and potatoes” (although this probably should have been “I want a quick dinner using roast chicken and potatoes”) when roasting takes an hour:

- High Agency: Suggests a different quick chicken recipe

- Medium Agency: Asks “Roasting takes 1 hour. Okay, or prefer something faster?”

- Low Agency: Gives the roasting recipe, ignoring the “quick” constraint

Your prompt needs to define this agency level explicitly, as it fundamentally shapes user experience. This is interesting, this feels a little bit different to me and I’m looking forward to seeing more as we go on.

Reference-Free vs Reference-Based Metrics

To finish up the lesson, we discussed two different approaches to evaluation:

Reference-Free

Checking output properties without comparing to perfect answers

- “Does the output contain an ‘Ingredients’ section?”

- “If user states an allergy, is the allergic ingredient absent?”

Reference-Based

Comparing generated answers against golden standards - useful for CI/CD workflows but less relevant for most production traces.

thingsithinkithink

-

The Three Gulfs looks useful. Thinking back to previous projects, I can now retrospectively identify which gulf caused specific failures. This might help me communicate to clients in the future.

-

The agency concept is new (to me) and might be important. Mulling it over. Not sure what I think yet - but it’s provocative.