Like a Ragged Prayer

Some interesting stuff from Alexandra Alter on how AI is disrupting the romance novel industry.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 6 min read

This week’s Hard Fork featured an interview with New York Times reporter Alexandra Altar, who wrote a piece about how AI is disrupting the romance novel industry. It’s the pulpy end of the fiction spectrum - so presumably the community of creators here might self-identify less as Artists (with a capital A) - but this community is wrangling with the impacts of AI just like everybody else, and in some ways they’re further along than most.

Romance has always been a high-output genre - prolific writers publish multiple books a year. But one writer profiled in the piece, Coral Hart, has gone from about ten books a year to over two hundred, using AI across twenty-one different pen names. She made six figures doing it.

Not the reaction you’d expect

I was expecting to hear a story about how threatened romance novelists feel. I was expecting to hear how unethical it is that AI trained on all of their creative works. I was expecting to hear about how any novel created using AI would be devoid of value. But there was a lot more nuance than I anticipated, and there are a couple of interesting things worth sharing.

The romance writing community didn’t seem to show the same pattern I typically see in other creative communities - at least not uniformly. In most creative communities I spend time in, the public-facing consensus is almost universally anti-AI. That’s not the case here. Some of the writers Altar spoke to were very enthusiastic about using AI for novel writing and have started to develop surprisingly sophisticated processes for creating their books. They know which models are good at what. They’ve developed blocklists for words that LLMs overuse. They’ve built prompting strategies that go well beyond what your average ChatGPT user would think to do.

One of the writers describes herself as less of a writer now and “more of a director, a creator.” She comes up with the plots and the characters, but she doesn’t think of herself as the author anymore.

This will feel very familiar to any techies who have been paying attention to AI’s impact on software engineering. As many have commented, individual programmers are writing far fewer lines of code than they were a year ago. A lot of what they do now looks more like code review - or more like software engineering management than software engineering directly. In my Typing Code and Punching Cards post, I wrote about Simon Willison’s prediction that the job of being paid to type code into a computer will go the same way as punching punch cards. Programmers are spending more time planning, specifying, and verifying than they are writing - moving up the stack in much the same way Coral Hart describes moving from writer to director.

The relentless pull of the mean

The interview also highlighted some of the genuine downsides of using these tools for creative writing. Left to their own devices, LLMs default to boring, generic, and repetitive. The writers have discovered that without careful steering, the AI will set every love scene in the bedroom or the shower. It’ll jump straight to the climax of a scene without any buildup. And it has a stubborn fondness for certain phrases.

For example, the phrase “he whispers her name like a ragged prayer” (and very similar variants, e.g. “jagged prayer”, “rough prayer”) appears repeatedly within and across entirely different books from different authors. This has led writers to block the phrase entirely because the AI won’t stop using it.

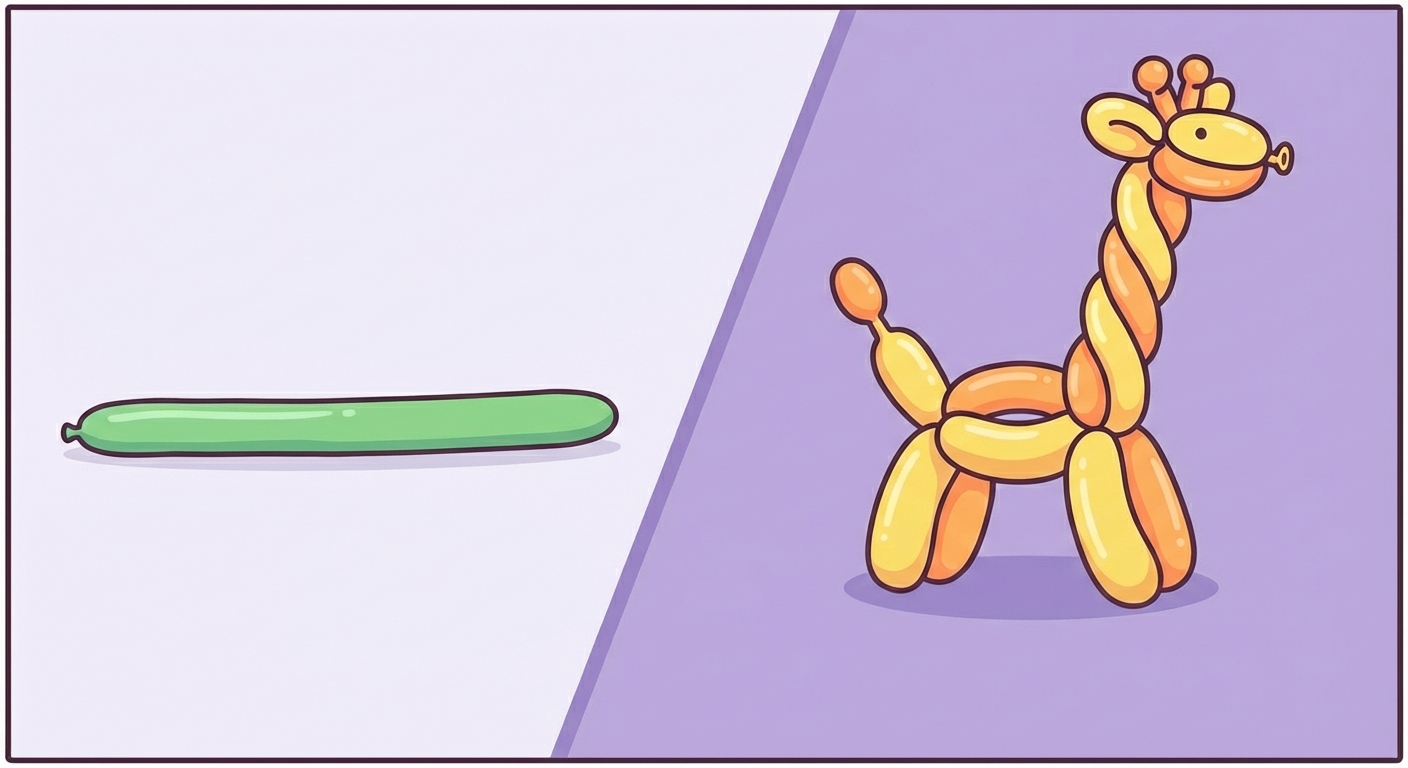

This is obviously a problem with these tools, and I’m pretty sure any heavy user of them has discovered it. If you don’t actively fight against it, the desire of these models to regress to the mean is incredibly strong. When I coach on how to use AI, I use the analogy of a balloon animal. If you pass an LLM a balloon and say “give me back a balloon animal”, it will blow it up and give you back a snake. Whereas if you were to partially blow up the balloon - tie two legs at the back, and another two legs close to the front, leaving a lot of balloon after those legs - the LLM will create a giraffe. I think of the job of prompting as being about getting giraffes every time. We want opinionated outputs, not snakes.

We want more giraffes and fewer snakes

We still haven’t figured out how to handle copyright

Also interesting is the acknowledgement from publishers that they will eventually be acquiring AI-assisted books, if they’re not already (and I’m pretty sure they are already). Most publishers have existing contract clauses requiring authors to assure that their work is “original” - but what does that mean when AI wrote significant portions of the text?

Content produced by AI currently can’t be copyrighted, and publishers don’t want to put out books they can’t protect. This is a question I think many other industries are going to have to grapple with too - what it means to hold intellectual property rights over something that was co-created with an AI.

Two game industries, two very different vibes

Most of my previous career was spent in and around game development, and I’m still connected to lots of people who work in games. The overwhelming consensus view in the indie games community is that AI is a negative - a soulless vampire that sucks all creative value from any project. This is a view you see online and in most creative communities I’ve come across or spent time in. When I work with companies, I often find this perspective in their graphic design and similar departments as well.

But I was at an industry event a few months ago attended mostly by people working at large game companies and publishers. The perspective was very different. Pretty much every company was already using AI in many places and saw it as an inevitable productivity tool. There wasn’t angst about whether to use it. They were well past that and into the practicalities of how to use it effectively. Obviously this is because these large companies are run primarily as commercial endeavours rather than creative endeavours - but the individual creators working on their projects didn’t feel the same resistance even in principle. They saw AI as just another part of the stack, no different to other tools they use for game development.

thingsithinkithink

-

I think 2026 might be the year where the resistance to AI - the desire to put it back in the box - meets the commercial realities of the performance and productivity gains it offers, in a way that forces some maybe high-profile conversations.

-

Maybe a huge game comes out, it’s a massive hit, and it’s clearly got a lot of AI inside it. How does the games community resolve that tension? The same thing is probably going to happen with movies. Probably with music. The romance novel industry is just getting there first because the genre’s economics and templates made it the path of least resistance.