LLM Evals Lesson 8: Improving LLM Products

Notes from the final lesson of Hamel and Shreya's LLM evaluation course - practical strategies for improving accuracy and reducing costs through prompt refinement, architecture changes, fine-tuning, and model cascades.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 10 min read

The final lesson of Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s LLM evaluation course covered practical strategies for the “Improve” phase of the evaluation lifecycle. This post focuses on that lesson content in detail.

Improving LLM-Based Systems

With analysis and measurement complete, we can finally focus on improving our system. The lesson covered two areas: accuracy optimisation and cost reduction.

Improving Accuracy: Quick Wins

Quick wins close the Gulf of Specification. If you’ve done error analysis properly, you’ll probably find a bunch of quick wins. You thought the system worked a certain way, you discovered it doesn’t, and often the fix is straightforward.

Prompt refinement: Clarify ambiguous wording. Add targeted few-shot examples for specific failures. Use role-based guidance.

On role-based guidance: there’s been commentary recently following research from Ethan Mollick’s team showing that expert persona prompts don’t improve factual accuracy. If you say “you are a genius math wizard” versus “you barely passed maths”, there’s no measurable difference in performance.

But that doesn’t make role-based guidance useless (so I disagree slightly with the great Simon Willison here). The benefit isn’t about inducing accuracy. It’s about inducing perspective. A tax adviser has a certain epistemic frame (a concept from David Williamson Shaffer): they’re concerned about certain things, looking for certain patterns, communicating in certain ways. Telling an LLM it’s a school teacher versus a tax adviser changes how it responds in ways that matter for your use case. Different, not more accurate.

Step-by-step reasoning: Adding examples of how to think through problems can improve performance on tasks requiring logic or planning. Though with reasoning models now available, this has become less critical. There’s even evidence that chain-of-thought prompting can harm reasoning models, and OpenAI’s own guidance notes that instructing the model to “think step by step” may not enhance performance and can sometimes hinder it. If you’re not using a reasoning model, it’s probably still valuable. If you are, there’s more nuance than the slide suggests.

Improving Accuracy: Medium-Effort Changes

Medium-effort changes impact architecture more significantly.

Task decomposition: Breaking a complex LLM call into a chain of smaller, focused calls. I had to do this on a recent Foreign Office project. People don’t really ask direct questions. They describe their situation in a paragraph, and often there are two or three separate questions buried inside. We built a stage of our pipeline that decomposes the original paragraph into up to three separate intentions, rewrites each as a focused query, then answers them separately rather than all at once.

Start simple though. See if your system can handle things in one go. If it can’t, then decompose.

Tuning RAG components: Often the problem is retrieval, not generation. The slide mentions chunking strategies and number of documents retrieved. In my experience, a common issue is assumptions baked into RAG implementations. People use vector similarity search and don’t leave space for keyword search or BM25. Revisiting those assumptions, trying hybrid retrieval mixing old-school keyword search with semantic search, can help considerably.

Fixing tool misuse: Tool descriptions, parameters, and expected formats matter. One thing I really like about MCP is that it advertises tool descriptions. I was recently working on a system connecting an MCP server to a Microsoft Copilot agent. I realised I could shift complexity into the tool descriptions and patch the live system without redeploying code, because the agent reads tool descriptions when they change. I can add parameters, tweak function names, give more context on choosing between tools. It’s a low-friction way to iterate. The Gulf of Specification applies to tools as well as prompts.

Improving Accuracy: Advanced Strategies

Fine-tuning: Use when you have hundreds of high-quality labelled examples for a recurring failure that prompting can’t fix. It’s more expensive and you need to continually fine-tune as base models improve. Shreya made the point that you fine-tune 3.5 to match 4, then 4 comes out and beats your fine-tune anyway.

I expected when I started working with LLMs that I’d be doing lots of fine-tuning. I spent time last year fine-tuning a Llama model on government content guidance. I got close to parity with OpenAI endpoints, but it was so much work (not the training itself, but organising the data, curating it properly, ensuring the right diversity, etc.), and if anything changed we’d have to redo everything. In practice, I’ve never actually needed fine-tuning in the wild. Architecture, tool descriptions, and prompting have always been enough. Fine-tuning makes sense for high-volume narrow tasks where you want performance and deployment cost benefits from a small model. But you also need institutional MLOps maturity to host, deploy, maintain, and keep it updated. Unless you’re fundamentally an AI company, you probably shouldn’t build those capabilities.

Systematic prompt optimisation: Tools like DSPy treat the prompt as a tunable artefact. I keep expecting this to be really valuable, and so far I haven’t been convinced. I think you need to be very mature in your understanding of your system to benefit. Things move so fast. I’ve only dabbled, so I can’t say definitively, but it feels like a dead end for now (to me, although I expect to be wrong at some point here).

Human review loops: For high-stakes tasks, build interfaces for regular human review to constantly feed new examples into your datasets. This is the one advanced strategy I’ve actually used. On the Foreign Office project, we built an interface so staff could maintain the dataset and tweak rules that end up in the prompts. They don’t know they’re prompt engineering, but they are.

Cost Reduction: Simple Strategies

The simplest approach: use the cheapest model that can get the task done.

The way I work: get the system running with whatever model I can, then swap out AI components for cheaper alternatives. Classification tasks don’t need GPT-5 or Claude Opus. On the Foreign Office project, we used GPT-3.5 for task decomposition and headline selection, but GPT-4 for the actual question-answer matching because 3.5 couldn’t handle it.

In my current gig, I’m happily using GPT-5 with thinking during prototyping, but I’ll swap to non-reasoning or smaller models for production.

Reduce token count: Consider how you want the LLM to respond. One or two word answers where appropriate. Use compact formats like YAML or XML instead of JSON if you’re not doing tool calling.

Leverage caching: Structure prompts with static content first, dynamic content last. This maximises cache hits.

How KV Caching Works

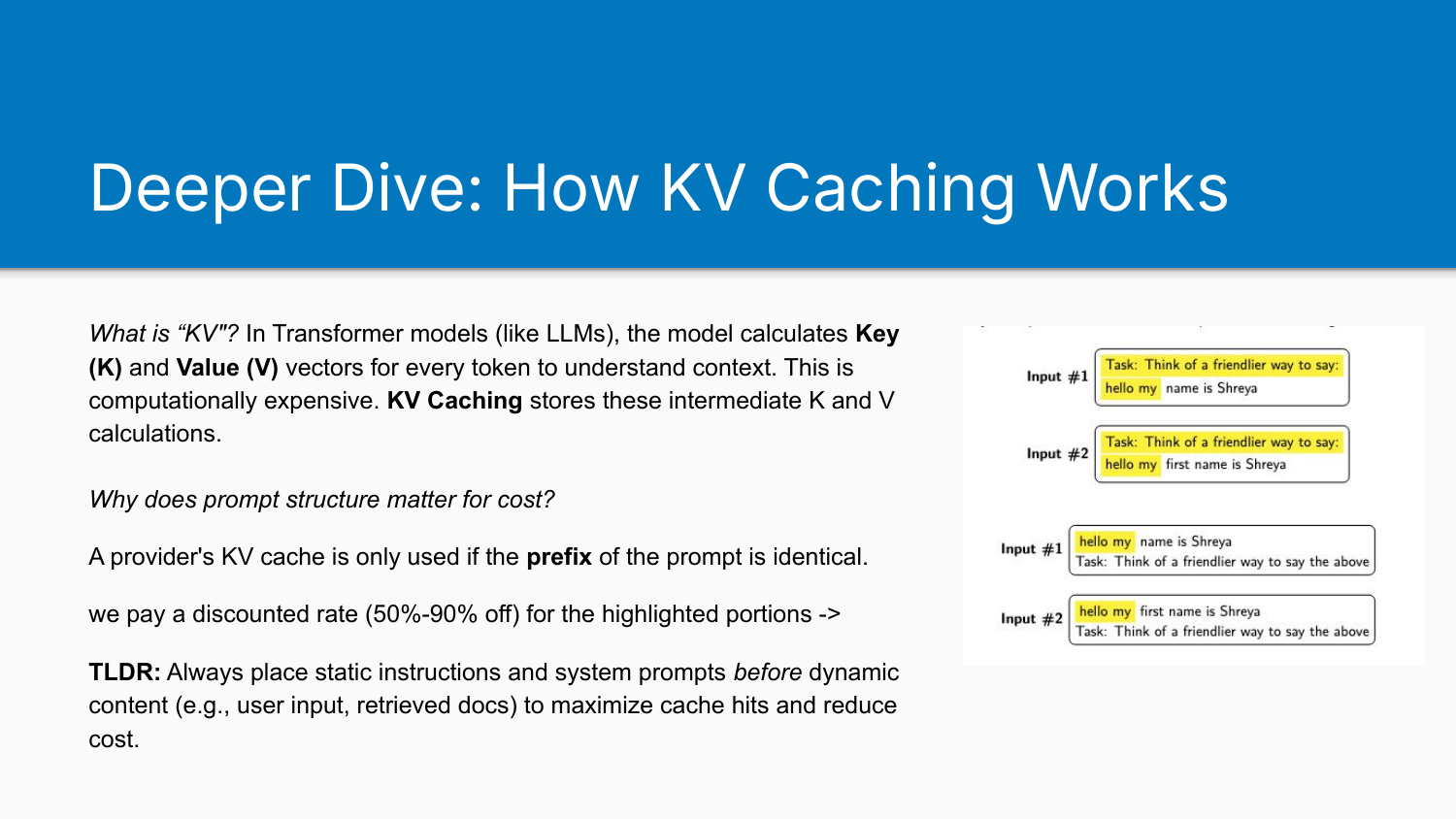

The slide on KV caching assumes you know what Key and Value vectors are.

In Transformer models, the model calculates Key (K) and Value (V) vectors for every token to understand context. This is computationally expensive. KV Caching stores these intermediate calculations so they don’t need to be recomputed.

A provider’s KV cache only helps if the prefix of your prompt is identical. If you put the user’s question at the top and context below, the user question won’t be cached and you branch into a different pathway immediately. Put context first, user question last, and you get all those cached tokens before branching on the new content.

What Caching Actually Saves

The discounts are substantial. Here’s what the major providers currently offer (as of 21st December 2025):

OpenAI: Up to 90% off input tokens on cache hits, model-dependent. GPT-5-mini cached input is $0.025/MTok versus $0.25/MTok standard (90% reduction).

Anthropic (Claude): Cache reads are 0.1× base input price (90% off). Cache writes cost more: 1.25× base for 5-minute caches, 2× base for 1-hour caches. Claude Sonnet 4.5 base input is $3/MTok, cache hits $0.30/MTok.

Google Gemini: 90% discount on Gemini 2.5 models, 75% on Gemini 2.0. Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite input is $0.10/MTok, context caching $0.01/MTok.

Batching adds another 50% discount across all three providers. Combined with caching, the reused portion can land around 5% of normal cost.

For example: 100 requests with a 10k-token repeated prefix, 1k new input, 1k output using Claude Sonnet 4.5. Without caching, input costs $3.30. With caching (paying for one cache write, then 99 cache hits), input costs roughly $0.63. About 81% input savings.

Hamel noted that you used to have to explicitly enable caching. Now it’s generally automatic. Here’s a minimal OpenAI example showing how to check cache hits:

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

# Needs to be long (>= 1024 tokens) for caching to kick in

STATIC_PREFIX = ("You are a concise assistant.\n" + ("background " * 2000))

def call(question: str):

r = client.responses.create(

model="gpt-4.1-mini",

input=[

{"role": "system", "content": STATIC_PREFIX},

{"role": "user", "content": question},

],

)

return r

r1 = call("Reply with exactly one word: hello")

r2 = call("Reply with exactly one word: goodbye")

print("cached_tokens call 1:", r1.usage["prompt_tokens_details"]["cached_tokens"])

print("cached_tokens call 2:", r2.usage["prompt_tokens_details"]["cached_tokens"])

See also Eleanor’s blog post on cost control.

Advanced Cost Reduction: Model Cascades

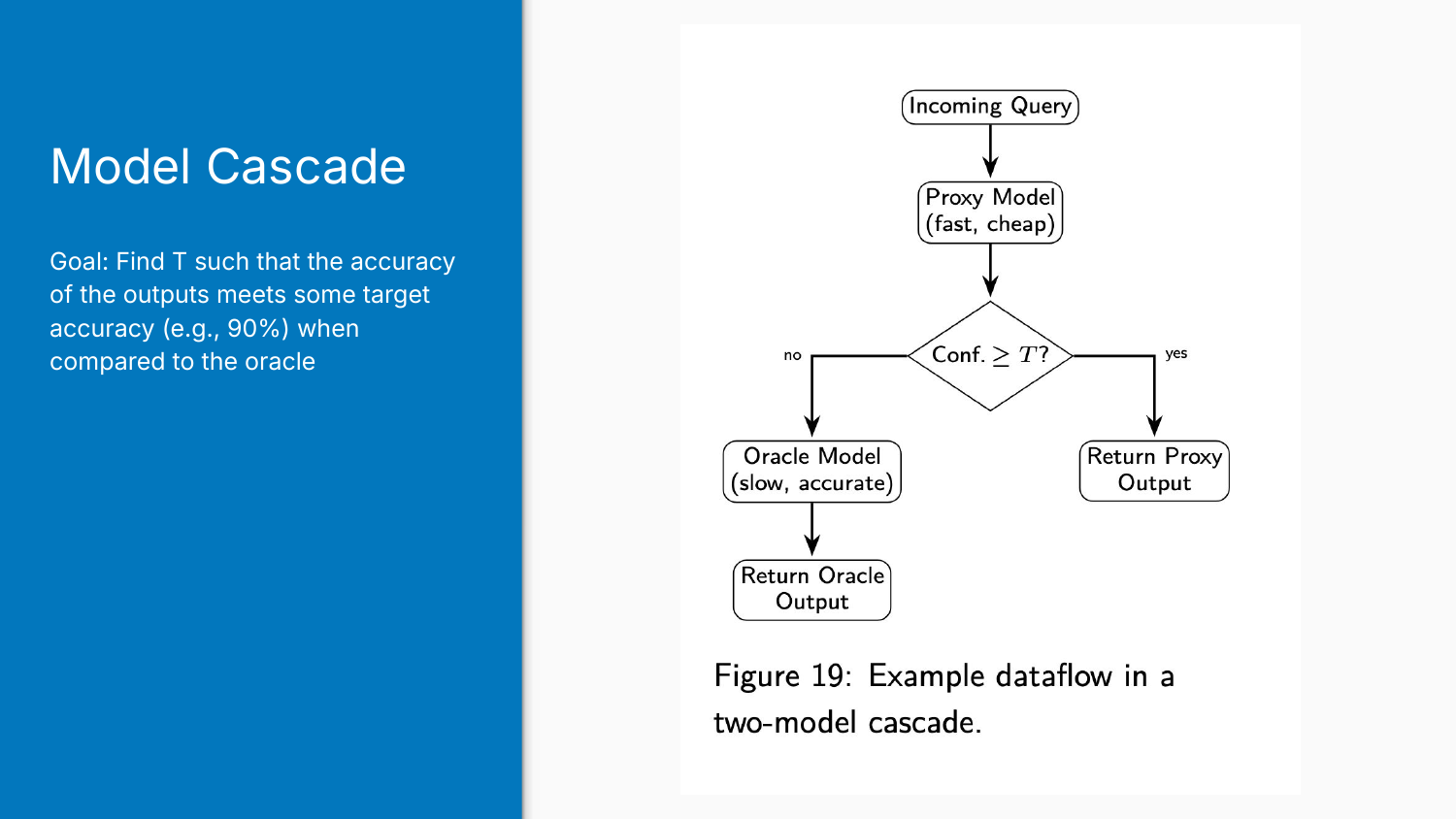

Model cascades route queries between cheap and expensive models based on confidence. The idea is basically to start with a cheap “proxy” model, and if it’s unsure, escalate to an expensive “oracle” model. Answer easy questions cheaply, save the expensive model for hard problems.

The goal is to find a confidence threshold T such that the cascade’s accuracy meets your target (say 90%) when compared to always using the oracle.

Log Probabilities and Confidence

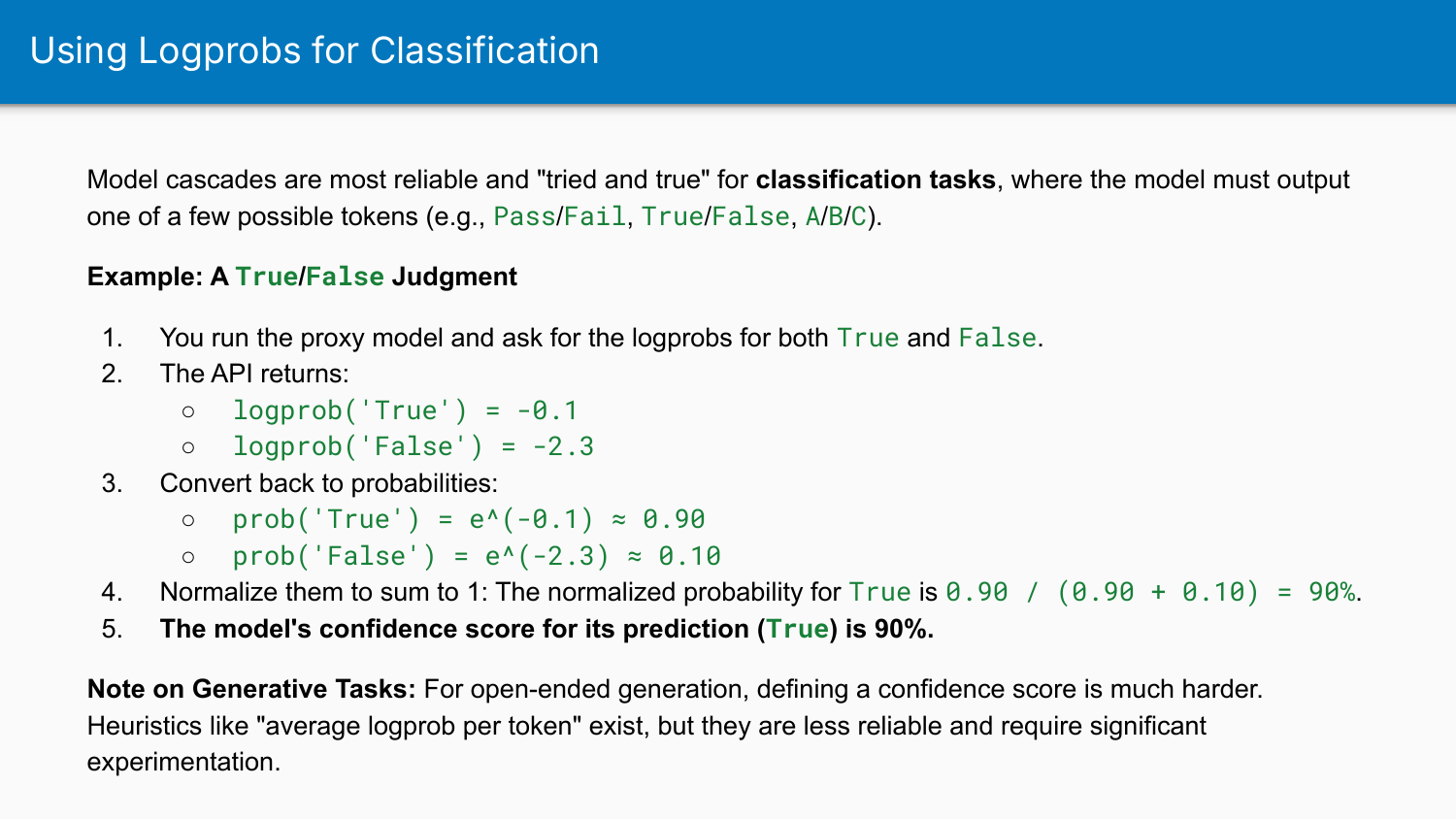

Most LLM APIs can return the log probability for each token generated. A logprob is the logarithm of the probability the model assigned to its chosen token. Values closer to 0 mean higher probability (higher confidence).

For classification tasks where the model outputs one of a few possible tokens (Pass/Fail, True/False, A/B/C), you can use logprobs to calculate a confidence score:

- Run the proxy model and get logprobs for each possible output

- Convert back to probabilities (prob = e^logprob)

- Normalise them to sum to 1

- The normalised probability for the chosen token is your confidence score

If confidence exceeds threshold T, return the proxy’s answer. Otherwise, escalate to the oracle.

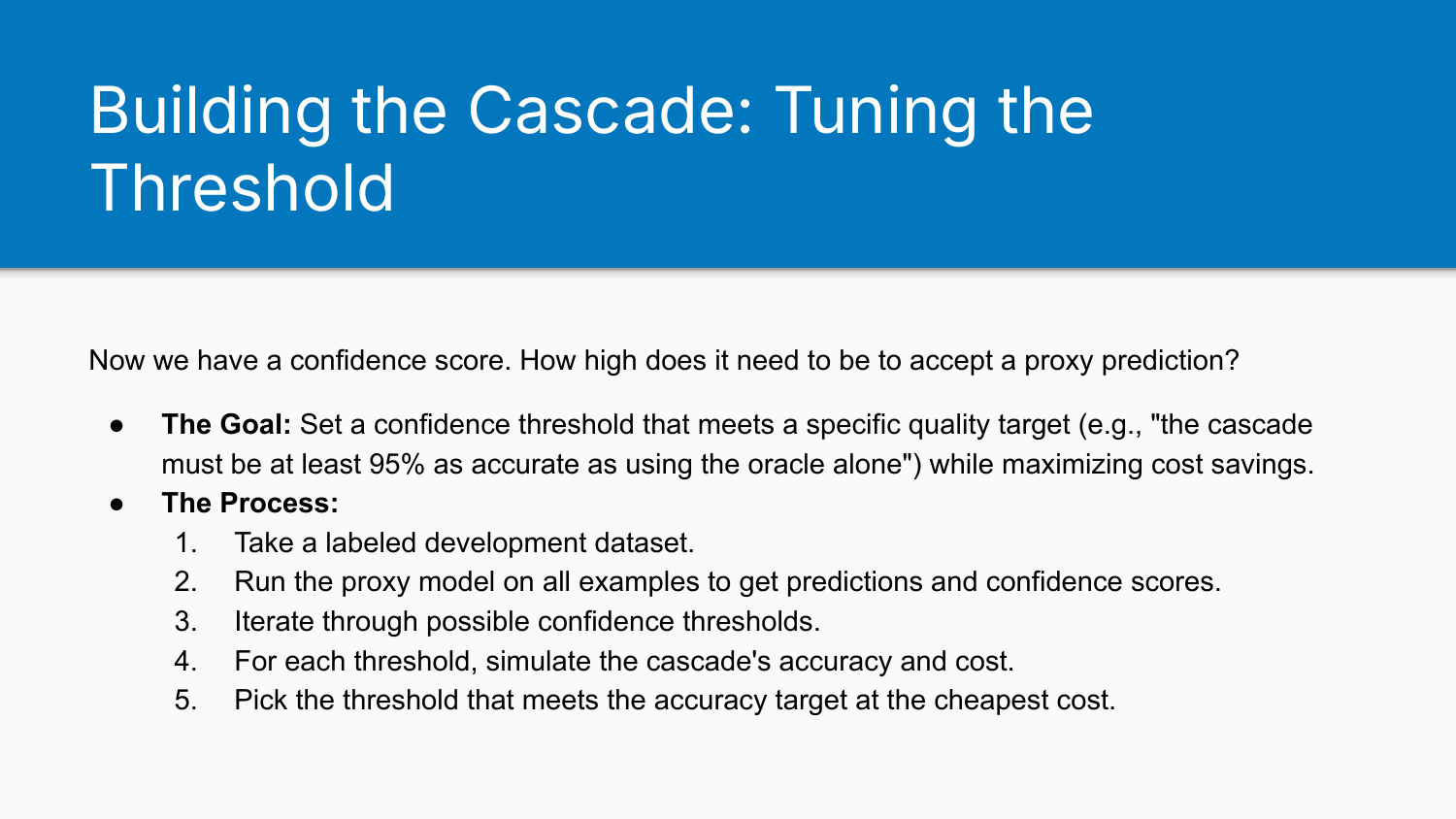

Tuning the Threshold

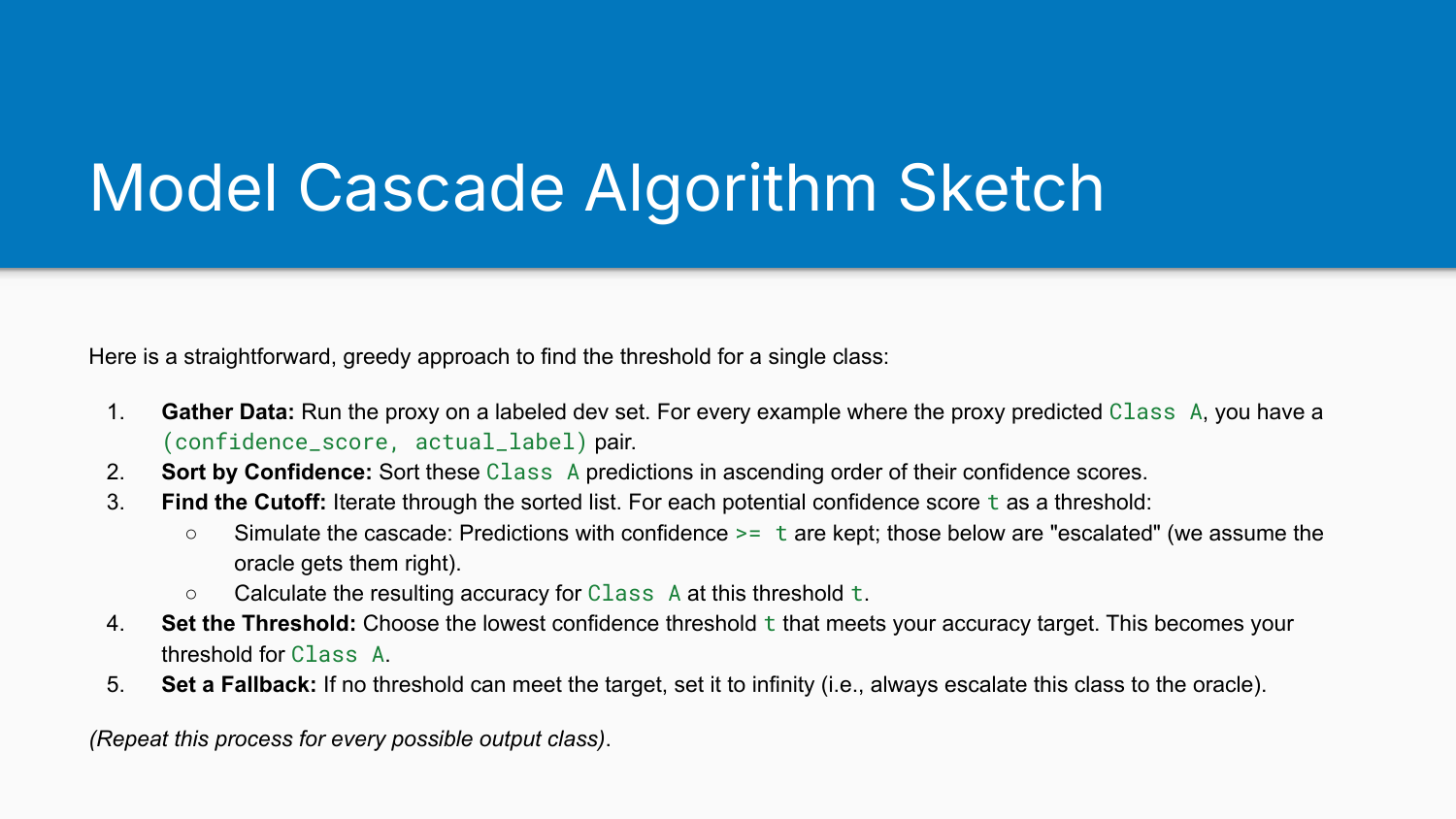

The process:

- Take a labelled development dataset

- Run the proxy on all examples to get predictions and confidence scores

- Iterate through possible thresholds

- For each threshold, simulate the cascade’s accuracy and cost

- Pick the threshold that meets your accuracy target at the cheapest cost

For generative tasks without discrete class labels, you treat all examples as a single group and evaluate the proxy’s output against a gold answer using a binary pass/fail judgement, often performed by an LLM-as-judge.

A Few Reservations About This Approach

I have fundamental issues with model cascades built on log probabilities.

The entire approach hinges on a strong relationship between model confidence and model correctness. I don’t believe that relationship is reliable. LLMs will confidently give you wrong answers. They do it all the time. Log probability measures something about the model’s internal state, but that something isn’t specifically truth.

Shreya acknowledges this is more reliable for classification tasks than generative ones. She finds value in binary true/false tasks. I understand why it works there, but I think it’s somewhat accidental. These are language models, not classification models. The logprob happens to correlate with correctness in narrow constrained cases, but it’s not exactly measuring what we want it to measure.

For open-ended generation, defining a confidence score is much harder. Heuristics like “average logprob per token” exist but are less reliable. And the majority of what people use LLMs for these days are generative tasks: conversations, unstructured data processing, content creation. Not simple classifications.

A good example of the limitations of this approach can be seen in the recent GPT-5 router debacle. One would assume it’s doing something like this under the hood, routing queries based on complexity. It didn’t really work well for them. If OpenAI can’t make it work reliably, I’m sceptical anyone can.

This doesn’t mean it will never be viable. But at this time, I’m not convinced. The recent OpenAI work on hallucination has similar ideas about training models to attend to their own confidence. I have similar reservations. These systems have a statistical probability-based architecture, not a logic-based one. We’re trying to force them to be something they’re not.

thingsithinkithink

-

Fine-tuning continues to be something I expect to need and never actually use. The institutional capability required to maintain fine-tuned models is substantial, and foundation models keep improving faster than you can fine-tune.

-

My scepticism about log probabilities as confidence measures extends to related ideas like training models to know when they’re uncertain. The architecture doesn’t support it. Statistical confidence isn’t epistemic confidence. I look forward to being wrong about this.

-

Role-based guidance remains useful despite the Mollick paper. Different versus more accurate. The epistemic frame of a persona shapes responses in ways that matter even if raw accuracy doesn’t change.