LLM Evals Course: Complete Course Recap

This is my recap of Hamel and Shreya's LLM evaluation course. I'm hoping I come back here in the future every time I need to remind myself of how to do this the right way.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 11 min read

I’ve finally finished writing up my notes from Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar’s LLM evaluation course. It took me longer to write up my notes than it took to actually do the course, but it gave me a good excuse to revisit everything a second time, which is a great way to help cement my learnings. I’m going to do one post here to finally capture the key things from each of the lessons, with the hope that I can refer back to this in the future to help me find the detail that I’m looking for.

Course Overview

The course covered eight lessons over several weeks. In this post, I’m going to give an overall reflection, but first here are links and summaries of each of the lessons:

-

The Three Gulfs Model & Evaluation Fundamentals - Introduces the core framework for understanding LLM development challenges and establishes the analyse-measure-improve cycle.

-

Error Analysis & Systematic Failure Identification - Teaches open and axial coding techniques from qualitative research to systematically discover and categorise failure modes.

-

Building Automated Evaluators - Covers creating reliable LLM-as-judge systems with proper data splits, bias correction, and calibration techniques.

-

Multi-turn and Collaborative Evaluation - Addresses conversation-level evaluation and building evaluation criteria through collaborative annotation with Cohen’s Kappa.

-

Evaluating Complex Architectures - Focuses on RAG systems, retrieval metrics (Recall@K, NDCG), and tool calling evaluation strategies.

-

Complex Pipelines and CI/CD - Covers debugging agentic systems with transition failure matrices and implementing continuous integration for LLM applications.

-

Interfaces for Human Review - Applies HCI principles to build custom review interfaces with strategic sampling approaches for efficient annotation.

-

Improving LLM Products - Provides practical strategies for accuracy improvement and cost reduction through prompt refinement, architecture changes, and model cascades.

The Three Gulfs Model

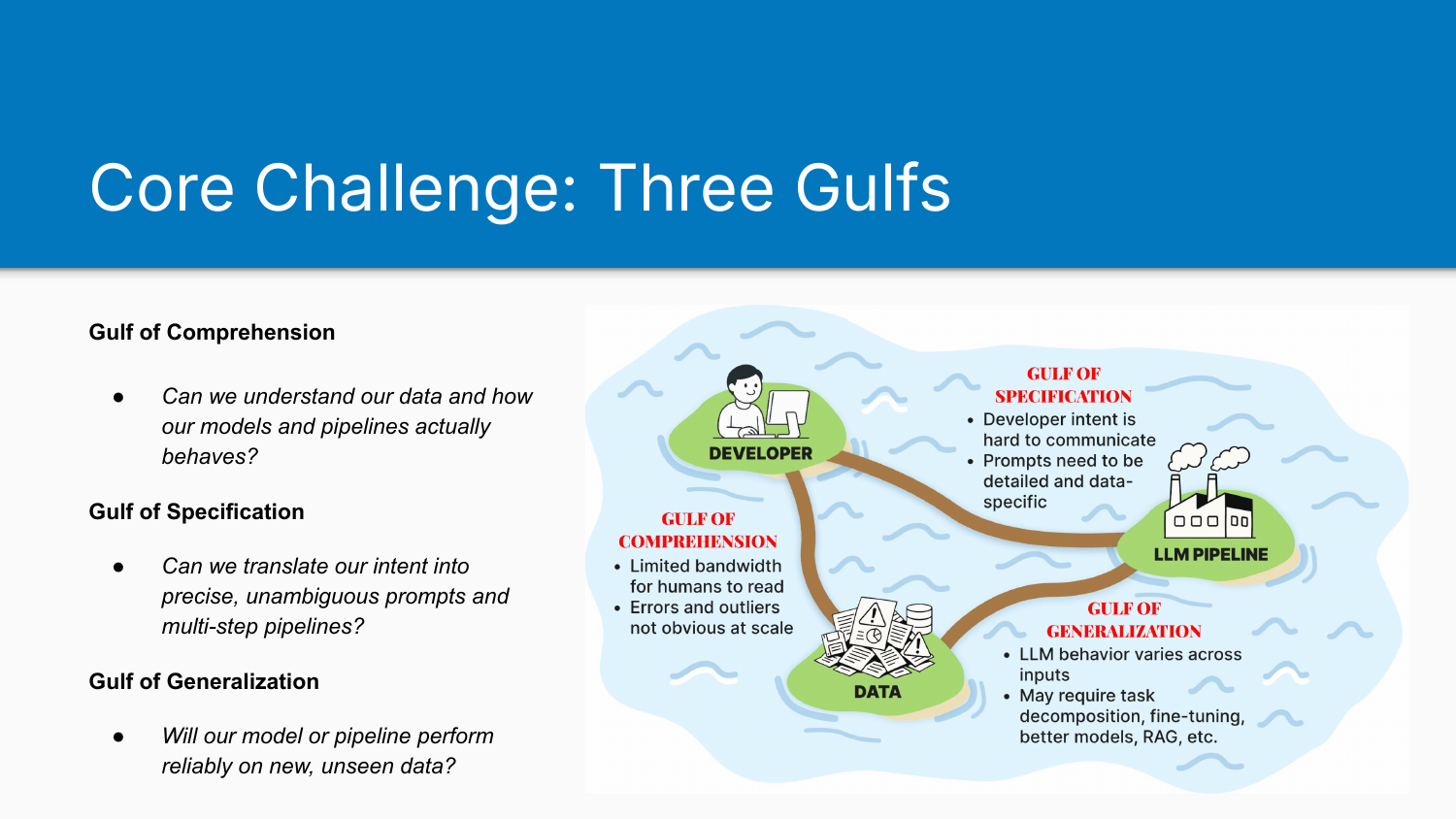

The course’s central premise is that building good LLM pipelines is hard because of three fundamental challenges.

The Gulf of Comprehension sits between the developer and the data. It’s hard to understand everything in your data: real user queries, system outputs, synthetic test cases. We end up with a partial model of what’s actually happening in our system. As Shreya put it, you can’t vibe check your way to understanding what’s going on.

The Gulf of Specification sits between us and the instructions we give the LLM. We’re trying to describe what we want, but much of our intent is latent. We only realise what we actually mean when we see outputs that inform us we need to specify better.

The Gulf of Generalisation sits between the LLM and the data. Even after specifying everything in detail, the model isn’t always good enough. When it encounters data outside its training distribution, it struggles to execute our specification. This requires different strategies: fine-tuning, task decomposition, RAG improvements.

LLM Agency Levels

A nice framing from Lesson 1 is to consider LLM agency - how much freedom you give the model to reinterpret user intent. High agency means the LLM actively reinterprets what users ask for. Medium agency means it asks clarifying questions. Low agency means it takes requests literally. You need to decide this explicitly in your prompts because it changes how users interact with your system.

The Analyse-Measure-Improve Cycle

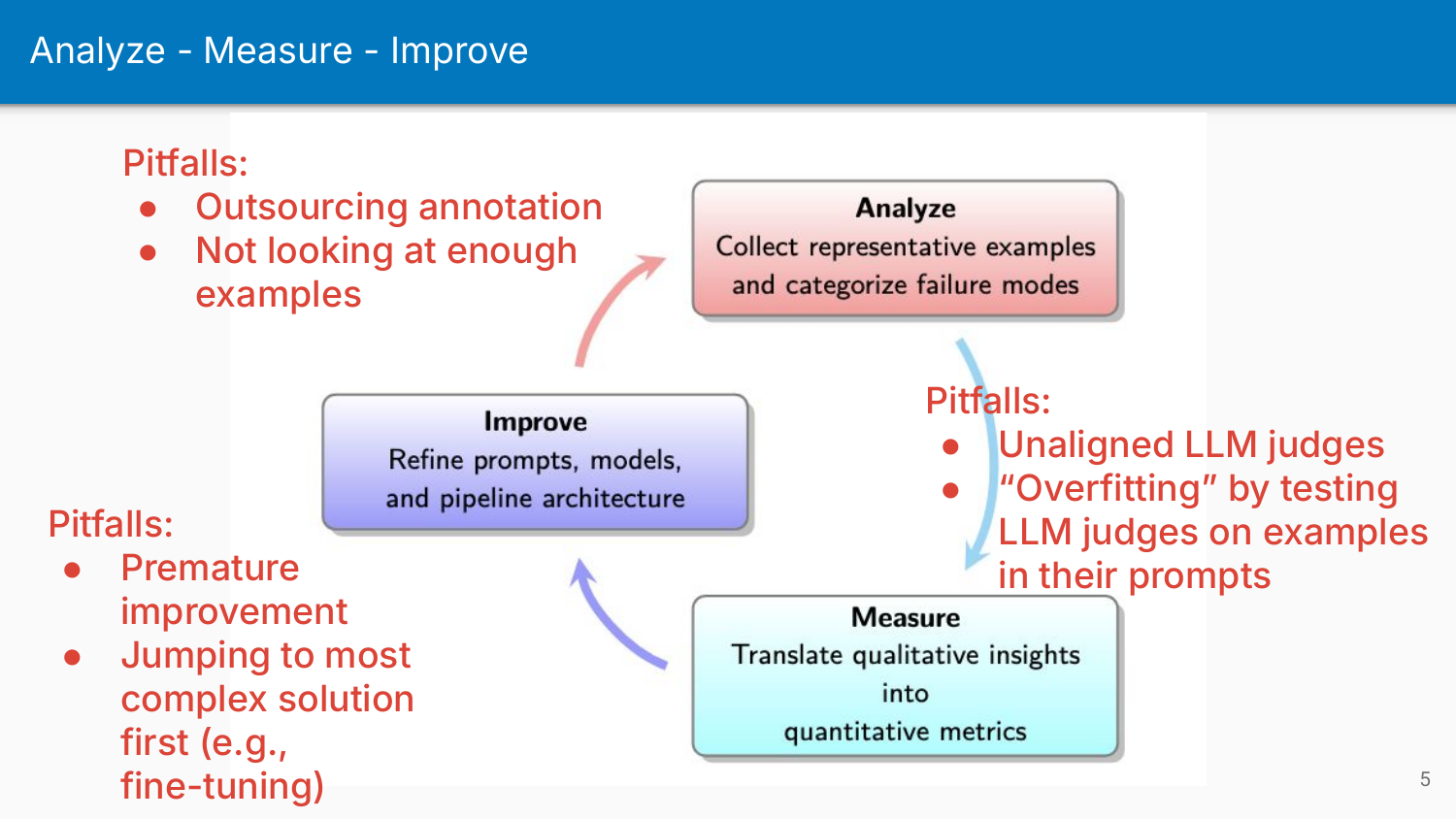

The course structured everything around a three-phase cycle, each with its own common pitfalls.

Analyse Phase: The goal is qualitative understanding. You’re looking at your data, identifying failure patterns, and building a taxonomy of what’s going wrong.

Pitfalls:

- Outsourcing annotation to the wrong people instead of owning it yourself

- Not looking at enough examples to reach theoretical saturation

- Using annotators without domain expertise - technically correct responses can still fail business objectives (Lesson 4)

Shreya repeated throughout the course that no matter the size of your company or product, you always have to do error analysis. The ease of doing error analysis now, and the specific process for doing it well, is probably the single most valuable thing to get from this course. The bang for buck on systematic error analysis is very high. When defining evaluation criteria, start with what makes users unhappy, then invert it - that gives you a practical foundation for what good looks like.

Measure Phase: The goal is quantification. Once you know your failure modes qualitatively, you need to measure how prevalent they are so you can prioritise and track improvement.

Pitfalls:

- Unaligned LLM judges that don’t reflect your informed perspective

- Data leakage by putting failure traces directly into your judge’s prompt, then testing on those exact traces

The second mistake surprises me that people make it, but apparently they do. If you put examples in the prompt and then test on those same examples, of course your judge performs well. That’s not overfitting so much as leakage.

Improve Phase: The goal is targeted fixes. With analysis and measurement complete, you can finally make changes with confidence that you’re addressing real problems and can verify whether you’ve made things better.

Pitfalls:

- Premature improvement before proper analysis and measurement

- Jumping to the most complex technical solution first

In my line of work, I meet lots of different clients who want help with some LLM-based solution. Those that know something about AI often demonstrate that second pitfall. It seems to me that the more people know, the more inclined they are to have an opinion about one of these complex technical solutions. Fine-tuning is a common example. They’ve heard of it, they can see a pattern match between their understanding of it and the problem at hand, and they want to go straight to it. But it’s usually far easier and cheaper to start with the smallest intervention, which is often just working on the prompts. Medium-effort options (Lesson 8) include task decomposition (breaking complex calls into focused chains) and fixing tool descriptions. Structure prompts with static content first and dynamic content last to maximize cache hits - providers offer roughly 90% discounts on cached tokens, and batching adds another 50% on top. Model cascades (Lesson 8) route queries between cheap and expensive models based on confidence thresholds, though reliability depends on correlation between confidence and correctness - which may not hold for generative tasks.

The Analyse Phase: Understanding What’s Broken

The analyse phase focuses on qualitative understanding through systematic error analysis:

- Bootstrap a dataset (real or synthetic). For synthetic data, use dimensional sampling (Lesson 2): identify dimensions that vary meaningfully (user intent, persona, query complexity), generate combinations across those dimensions, then convert each combination into realistic queries. This structured approach prevents the “procedurally generated soup” problem where you get lots of variation that all looks the same.

- Open coding: Read traces and apply descriptive labels to find failure patterns

- Axial coding: Cluster those labels into a structured taxonomy of failure modes

Your understanding evolves as you review more data - this is called evaluation criteria drift (Lesson 2). The person who finishes labelling sees the data differently from the person who started (even though they’re the same human being). This means you have to go back and re-label from the beginning, iterating until you reach theoretical saturation where new examples reveal no new failure modes.

For subjective criteria, collaborative evaluation with multiple annotators helps. The focus isn’t on figuring out who’s correct when there’s disagreement. It’s on improving your description of the criteria until everyone becomes aligned. Cohen’s Kappa measures agreement; alignment sessions refine the rubrics. When refining rubrics (Lesson 4), clarify vague criteria into concrete requirements, add illustrative examples, create decision rules for edge cases, and split criteria when one measure tries to do two jobs. Use binary yes/no evaluations for failure modes rather than Likert scales - it’s much harder to reliably distinguish between a 2 and a 3 than to answer whether something failed or not.

The Measure Phase: Quantifying Failures

Once you know your failure modes, you quantify their prevalence through automated evaluators. Evaluations fall into two categories (Lesson 1): reference-free (checking properties without comparing to perfect answers) and reference-based (comparing against golden standards).

Programmatic evaluators are fast, cheap, and objective. If you’re checking whether your system used a tool, you don’t need an LLM judge. Just check if the tool object is populated. Regex, schema validation, keyword matching all fit here. For agentic systems with tool calling (Lesson 5), check each stage separately: tool selection, argument generation, execution success, and output processing.

LLM-as-judge handles subjective or nuanced criteria. But a trustworthy judge isn’t automatic. You have to build and validate it.

Judges aren’t perfect, and their imperfections create bias in your metrics (Lesson 3). Use bootstrapping to calculate confidence intervals around your success rate estimates. The judgy library (Hamel and Shreya’s open-source library) implements bias correction formulas that adjust for known judge tendencies.

The judgy library helps you calibrate an LLM judge when you know it sometimes mislabels things. You run the judge on a small human-labelled calibration set, estimate its false positive and false negative rates, and then apply a correction so your reported pass rate is closer to the truth. It is most useful for binary pass/fail style metrics and assumes the judge’s error rates stay broadly stable, so it will not fix broader issues like preference for certain writing styles, position bias, or shifts in behaviour over time.

To build and validate your judge, the approach mirrors ML training: split your labelled data into train, dev, and test sets. Don’t leak data between them. The analogy is slightly forced since these don’t map exactly to how you’d use them in a traditional ML pipeline, but the principle holds. The “training set” here means a handful of few-shot examples in your prompt. The dev set is what you iterate on while refining the judge. The test set stays sealed: you know the human labels, you run your judge, you measure TPR and TNR, but you don’t peek inside to improve the prompt. Poor TPR means you underestimate your system’s performance; poor TNR creates false confidence (Lesson 3).

Multi-turn Evaluation

For conversational systems, freeze the messages array at failure points to create test baselines (Lesson 4). Test perturbations like intent switches and added constraints to check robustness. Include conversations of varying lengths in your test set - performance often degrades over longer exchanges.

RAG and Tool Calling

For RAG systems, evaluate retrieval and generation separately before end-to-end testing (Lesson 5). Check retrieval with Recall@K - is the right context available? Then evaluate generation for faithfulness to retrieved context and relevance to the original query.

Operationalising Evaluation

Making evaluation part of daily workflow borrows from CI/CD thinking.

Continuous Integration: Create a golden dataset of critical examples and known failure modes. Every time you change something, run evaluators to create a regression safety net. If you accidentally made something worse, you’ll know. For agentic systems, use a transition failure matrix to identify which state transitions fail most - this reveals debugging priorities (Lesson 6).

I recently heard on Latent Space that in practice, most teams now don’t handcraft golden datasets from the start. They put systems in the wild and collect traces as they go. Either way, you end up with something to test against.

Continuous Deployment: Monitor a sample of production data continuously. Track performance. Try to uncover unknown unknowns before they cause problems. This might mean floating thumbs up/down on a percentage of uses, with too many thumbs downs immediately flagging something for people to look at. Or it could be grabbing a percentage of production data, human-labelling it, comparing it against system performance, and checking whether you’re broadly in line with where you’d expect to be. The goal is to make sure things are on track and you haven’t drifted too much. Distinguish between async evaluations (slower, diagnostic, sample-based) and guardrails (fast, reliable, real-time intervention) - they serve different purposes (Lesson 6).

LLM judges drift as models and user behavior evolve - re-evaluate every few weeks (Lesson 6).

Human Review Interfaces

The course made a big deal of building custom interfaces for reviewing LLM output data. Spreadsheets and generic log viewers don’t account for the specific shape of your data. Custom interfaces provide roughly 10x review throughput - 200 traces per hour versus 20 in spreadsheets (Lesson 7). Apply Jakob Nielsen’s usability heuristics: progress bars motivate completion, single keypress for pass/fail speeds review, pre-filled failure mode options reduce cognitive load (recognition over recall), and allowing deferral of uncertain cases prevents getting stuck. Blend random sampling (health check), uncertainty sampling (low-confidence cases), and failure-driven sampling (violations, bugs) - aim for around 100 traces per week.

I really love this, and I’ve been doing it ever since. Before the course, I used to do this the hard way, evaluating all of my data in spreadsheets. It was a total pain in the butt, and I really appreciate how much better a custom interface can be. It’s one of my big takeaways from the course alongside the error analysis methodology.

thingsithinkithink

-

The error analysis methodology and custom review interfaces are my two biggest takeaways from this course. I was doing versions of both before, but without the mature perspective the course provides. It was a pain in the arse the way I used to do it. This is better.

-

The Three Gulfs model gives a useful vocabulary for diagnosing where things are going wrong. Is it comprehension (I don’t understand my data)? Specification (my prompts aren’t clear enough)? Generalisation (the model just can’t do it)? Having that language helps.

-

This was some of the best money I’ve spent on a course in recent memory. The downside is it took forever to write up blog posts about each lesson. I haven’t had time to write up notes from two other courses I enjoyed this year: Elite AI Assisted Coding by Eleanor Berger and Isaac Flath, and How to Solve it With Code by fast.ai/Answer.AI, led by Jeremy Howard with Eric Ries.