The Jevons Paradox and the Kindle Web Proxy

When solving problems becomes almost free, more problems get solved. I built a silly little app last night that nobody else would ever build, and that's sort of the point.

- David Gérouville-Farrell

- 5 min read

I have a Kindle Oasis that I’ve had for years and I love it. I really love reading, I feel good about myself when I read more, but I struggle to resist the allure of the internet and the ease of access that my phone gives me to a never-ending slot machine of interesting things.

The Kindle Oasis has just enough connectivity built in to be useful. Long press a word and you can look it up in the dictionary or check Wikipedia. Occasionally I’d want to understand something from a book a bit better and I’d open the Kindle’s web browser to look it up. The browser used to be labelled “experimental” and while they’ve dropped that label, it’s still very bare-bones. Most modern websites render fine, albeit they don’t perform very well, but it’s not really been something that bothered me until recently.

BBC News rendered directly on the Kindle - garbled text and broken layout

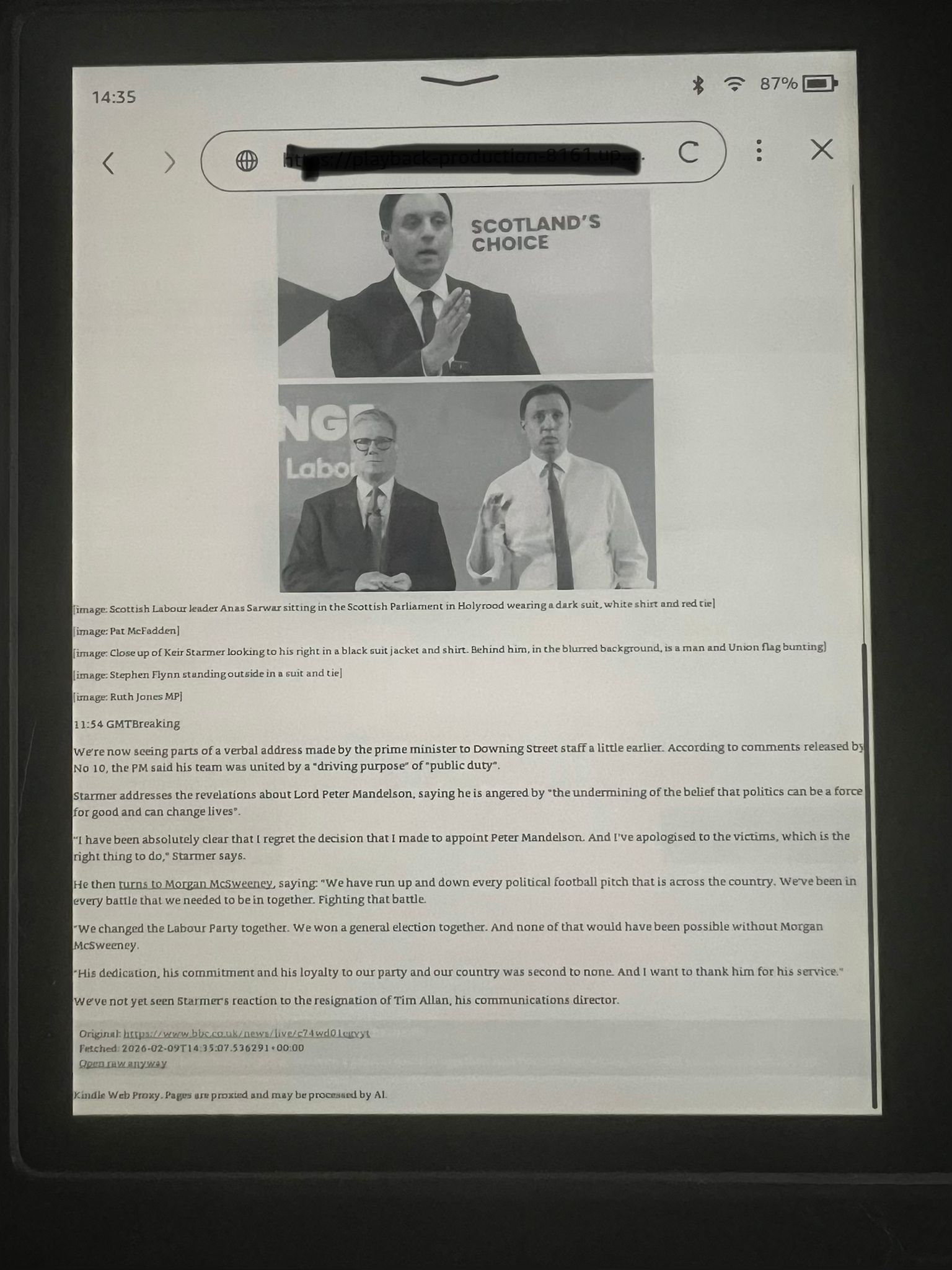

The same page through the Kindle Web Proxy - clean and readable

These days, though, I sometimes come across concepts that Wikipedia doesn’t cover well enough, and what I really want is to ask an AI about them. The Kindle can’t do this. None of the main AI websites work on it. Additionally, I love taking my Kindle with me to the sauna, and you don’t take your phone to the sauna, which means I can’t access my passkeys for OAuth anyway, even if the frontier lab websites did render correctly on it.

My Niche App

Last night I solved this problem by prompting AI maybe 20 times as I cooked dinner. With the help of Claude Code, I built a Kindle Web Proxy - a server-side web proxy that makes the modern web readable on e-ink.

It’s a Flask app that sits between my Kindle and the internet. You get a simple input box and you can do three things with it:

The home page - type anything and choose Open URL, Search, or Ask the AI

- Enter a URL directly - the proxy fetches the page, strips out all the JavaScript, ads, and complex layouts, and returns clean HTML that the Kindle can actually render

- Search the web - it searches via Brave Search and lets you browse results through the proxy

- Ask AI - you can have a multi-turn conversation with Google’s Gemini 3 Flash Preview about whatever you’re reading

Search results for ’the second opium war'

Wikipedia article rendered through the proxy - with images, working links, and an AI cleanup option

Asking the AI about the Second Opium War

It also handles images (converts to greyscale, resizes for e-ink), paginates long articles so the Kindle doesn’t choke, and even extracts text from PDFs. There’s a bookmarks system so I can save pages for later.

The whole thing is hosted on Railway at near-zero cost. Between Brave Search’s free tier (2,000 searches per month) and Gemini Flash being absurdly cheap, I will never come close to hitting any spending limits. I might use this app ten times a year.

The Jevons Paradox

I’m sure most folks who would land on this blog have heard of the Jevons Paradox by now, but I first came across it working on a climate change project, learning about how increasing the number of lanes on a motorway actually increases traffic rather than decreasing it. People have recently started bringing the Jevons Paradox into the tech world, and specifically to talk about AI. You can read about it on Wikipedia, but the idea is that when technological improvements make a resource cheaper to use, demand for that resource can increase rather than decrease, because the lower cost opens up applications that weren’t viable before.

Software’s Jevons Moment vs. Software Engineering Apocalypse

There’s a growing consensus among tech leaders that AI coding tools have crossed a meaningful threshold. Andrej Karpathy, in his 2025 year in review, described how code has become “suddenly free, ephemeral, malleable, discardable after single use” and predicted that “vibe coding will terraform software and alter job descriptions.” Dario Amodei, Anthropic’s CEO, told the World Economic Forum in January 2026 that AI could handle “most, maybe all” of what software engineers currently do within twelve months, noting that some engineers at Anthropic already “don’t write any code anymore” but instead let the model write it and focus on editing. Jensen Huang has been saying since 2023 that “everybody in the world is now a programmer” and that we should stop telling kids to learn to code.

I’ve felt this shift myself. I’ve been using AI-assisted coding tools since they first emerged, but something genuinely changed around November 2025. With Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.2-Codex, these tools became capable of generating high-quality software - given you wield them carefully. The improvement is immense and very real. This blog post is a case in point.

There’s a vocal camp that sees all this leading to the collapse of software engineering as we know it. A Stanford study found that employment for software developers aged 22-25 has declined nearly 20% from its peak in late 2022. Stack Overflow reported that 70% of hiring managers now believe AI can perform intern-level work, and tech-specific internship postings have dropped 30% since 2023. The junior developer pipeline - the traditional way people enter the profession - is under serious pressure.

And whilst I don’t doubt there will be some depressive effect - at least on certain types of roles and entry-level positions, at least in the immediate term - an alternative way this could go, and the way I personally believe it’s going to go, is towards a Jevons Paradox type moment. The ability to create software for close to free means the demand for software skyrockets. Simon Willison has been exploring this idea too - suggesting that as the price for writing code falls, the demand for custom solutions could massively increase, potentially resulting in greater demand for software engineers, not less.

thingsithinkithink

- Think about any piece of software you’ve ever used. It’s always designed for, at the very least, a persona of a group of people who are somewhat like you. It’s never perfectly designed for you. I think we’re entering the era of software that solves each individual person’s quirky, individual little needs - and I think that’s kind of cool.

- Tags:

- AI

- Coding

- Side-Projects

- Economics

- Feature